The fantastic initiatives that are creating City 2.0

TED (which not many people remember was originally founded by information architect Richard Saul Wurman in 1984) has expanded dramatically over the last years, from a single annual event to activities spanning a network of thousands of TEDx events, the TED-Ed educational network, the TED Prize, and now its City 2.0 initiative.

Part of City 2.0 this year is a project of 10 awards of $10,000 being given away to support local ventures that are making a difference. We are half way through, with now 5 awards being given.

The City 2.0 project site gives a full rundown of the winners. Below is an overview of the five fantastic projects.

Recycled Amusement

Transforming thousands of plastic water bottles into a park where kids can play and learn.

Ruganzu Bruno Tusingwire is an eco-artist creating a permanent park.

The seed for the amusement park was planted when Tusingwire got involved in eco-art as a student at Kyambogo University. He began meeting other local artists, and together, they made work out of a rampantly available and strikingly inexpensive material: garbage.

“Art is unifying,” Tusingwire explains. “We can use what is around us to create treasure, employment opportunities, and make the environment better. There is a wonderful world of possibilities before us.”

WikiHouse

Blueprints for everyday people to build their own homes using open sourced designs and locally sourced materials.

Alastair Parvin & Nick Ierodiaconou work in the fantastic 00:/ collective (of which Indy Johar, who I wrote about recently, also is a member). In this initiative they seek to make cities “for the 99%”:

They created a blueprint that would allow everyday people to build their own homes using open sourced designs and locally sourced materials. They posted their designs and assembly directions online and encouraged anyone to try it out, iterate on it, and upload their own ideas. Since they first initiated the project, five prototypes have been assembled.

I love this approach to “open source housing”, in which everything is open and shared.

Also see the Wikihouse.cc website and a descriptive video from the founders:

Better sanitation

Training everyday citizens to map the flow of water in their local to prevent the spread of cholera, a deadly bacterial infection.

Faisal Chonan is running a pilot in Rawalpindi:

Chohan and his tech team will train everyday citizens to map the flow of water in their local areas, give them bicycles so they can get around, and mapping devices so they can register their findings. Not only will citizens benefit from new job skills and increased public health literacy, but potential spots of contamination will be identified and targeted for clean up. Subsequent stages will include mapping hospital reports on water borne diseases, replicated this mapping work in additional cities, and involving government officials.

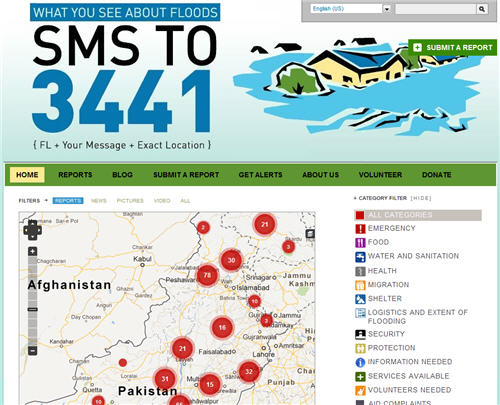

Here is an earlier project by Chohan in mapping flooding in Pakistan:

Crowdsourcing the Quiet

A web and smartphone based platform where people can crowdsource and geo-locate quiet spaces.

Jason Sweeney in Adelaide, Australia, believes that in fact crowds can allow us to find quiet.

“Some people think cities are only places of noise,” Sweeney explains, “but I think they have the potential to provide both chaos and calm.”

It’s much easier to find noise, at present, but Sweeney and his team of designers and artists are trying to change that through the Stereopublic project. With support from City 2.0 Award and the Creative Australia initiative, they will build an online space–likely web and smartphone based–where people can essentially geo-locate and crowd-source quiet spaces.

This is a personal favorite in drawing on crowd business models for good.

Lost in Lahore

A plan to install signage on the winding, eclectic streets of one of Pakistan’s oldest cities.

Asim Fayaz, Omer Sheikh, and Khurram Siddiqi will put help people find their way in a confusing city:

The signs they put up will follow international standards and have road names in Urdu and English. In addition to installing the new signage, they will also engage a team of paid experts and passionate volunteers to maintain the signs for a trial period of three months, documenting the time and effort required.

This will allow them to convince government officials of the sustainability of a scaled up effort to cover the most confusing parts of Lahore–many of which are also where the most interesting mosques and tombs are tucked away–with signage.