Strategic positioning in the flow economy: 3 action steps

Below is an excerpt from my book Living Networks that describes how to develop effective strategies in what I call the “flow economy” of information of ideas, where today almost all value resides. You can also download the complete Chapter 7 on The Flow Economy from the book website.

While the examples I used in the book are now a little dated, the strategic concepts are still absolutely relevant. I find that senior executives and strategists at my corporate clients continue to find the strategic planning process outlined here extremely useful. While the flow economy framework is most obviously relevant in technology, media, telecommunications, and services, it can be usefully applied in almost any industry.

Strategic positioning in the flow economy

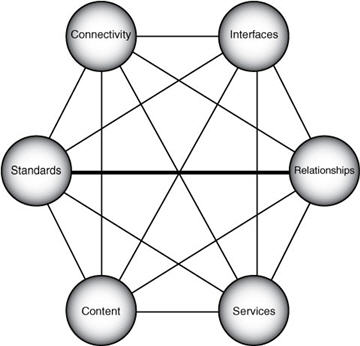

The six elements of the flow economy

Walk into a youth hostel or budget hotel in any exotic country around the world, and you’re more than likely to see someone reading a guidebook from Lonely Planet, the dominant global brand in budget travel. From its birth in the early 1970s, when Tony and Maureen Wheeler found so many people asking how they’d travelled overland from London to Melbourne that they decided to publish a book about it, the company has grown and repositioned itself neatly in the flow economy. The core of Lonely Planet’s business remains the publication of over 500 regularly-updated travel titles, however that is now complemented by a broad range of other business initiatives. The firm’s website attracts over two million unique visitors a month, providing free downloads of book updates that enhance the attractiveness of the guides, direct book sales sent from distributors worldwide, a highly popular discussion forum where readers share travel experiences, and access to Lonely Planet’s other services.

Lonely Planet launched CitySync in January 2000, providing in-depth guides to four US cities plus Sydney for mobile devices running the PalmOS operating system. The software and content, including interactive maps, can be downloaded on the Internet or purchased on CD-ROM or preinstalled modules. In addition to integrating city maps with reviews of hotels, restaurants, and nightlife, it integrates with other Palm functionality and enables users to add their own comments. As with Lonely Planet’s guidebooks, updates can be downloaded for free. Lonely Planet’s customers are by their nature on the move, so it seemed a natural fit to offer telecommunications services. Its eKno service provides not just low-cost international calls, but also global voicemail, faxmail, and voice notification of emails. In addition, Lonely Planet licenses its brand for a television travel series that is screened worldwide, and now it even publishes world music CDs. From publishing books, Lonely Planet has successfully diversified into providing telecommunications services and software in addition to a very wide range of content, and in the process built powerful direct relationships with its end-customers, which it never had before.

New approaches to business strategy are required as the economy begins to reshape itself. Almost every strategic tool in use over the last couple of decades is based on the increasingly dated concept of industries. Tools such as Michael Porter’s five forces model of competition are still applicable, but their value is fading because they are based on the concept of an industry as something static and defined. You must now consider your firm as a participant in the multi-dimensional space of the flow economy, rather than belonging to a particular industry. As you saw in Chapter 3, the issue is now how to extract value from your participation in a deeply integrated economic lattice made up of many players.

Earlier in this chapter we described how in the new convergence of the flow economy every organization will face new competition—often from unexpected quarters—and immense opportunities will unfold for those that recognize them. Firms must go through a constant process of strategic repositioning, founded on opening their thinking to dramatically new possibilities. Far more than at any time before, companies can participate in shaping the evolving structure of the economy. There is now immense scope for creative thinking—and leadership—in conceiving and forging entirely new forms of business. There are three core steps to this process of strategic positioning in the flow economy. We will study these steps, and then examine how to bring the strategic process itself to life.

STRATEGIC POSITIONING IN THE FLOW ECONOMY

1. Define your space

2. Redefine your space

3. Reposition

1. Define your space

To know where to go, first know where you are. Every company and industry will face different challenges and opportunities. Each firm must ask a number of strategic questions that will enable it to establish and implement a clear strategy. The key strategic questions for defining your current space in the flow economy are shown in Table 7-2.

STRATEGIC QUESTIONS FOR POSITIONING IN THE FLOW ECONOMY – I

Define your space

• What is the “total customer offering” in which you participate, and what is the value created for the customer?

• Who provides each of the flow elements that comprise the total customer offering, and what is the competitive landscape within each flow element?

• Which flow elements do you provide, and how are they combined?

• Are there any non-information elements to the offering, and who provides these?

• What alliances do you have with providers of other flow elements?

• What are your organization’s distinctive competences and strengths?

Table 7-2: Strategic questions for defining your space in the flow economy

The starting point is to define the “total customer offering” in which you participate. Since at this stage of the process we are examining the current strategic space, this should be the most obvious articulation of what customers receive. Only rarely do firms provide the entire customer offering. For example, newspaper publishers may frame their businesses as providing news to end-customers, and selling access to end-customers’ attention to advertisers. The other participants in this offering include newsagents, delivery services, and newswires; and if the newspaper has online services, a far more complex array of providers. Digitally-based customer offerings will always draw on every flow element in some form.

Let’s illustrate the strategic positioning process by taking a brief look at one major player in the flow economy, addressing the key strategic questions by examining each of the flow elements in turn. Nokia—and its peer mobile handset makers—at first view is a participant in providing the customer offering of mobile connectivity and services. Standards are the very basis of this mobile connectivity. Some standards—such as GSM (Global Standard for Mobiles)—are set by non-aligned industry bodies, and as such are essentially in the public domain. Nokia participates actively in the standard-setting process, both in order to have input to the technology, and to be fully informed on developments. It has made a strong public commitment to open standards, and has often worked closely with competitors and partners to initiate and develop other standards such as Wireless Application Protocol (WAP), that have promised to expand the use of mobile services. It is also a strong proponent of RosettaNet, described in Chapter 3. In most cases Nokia doesn’t provide connectivity; this is the role of its close partners, the telecom firms. Relationships with the end-customers are usually controlled by telecom providers, since they usually sell the handsets, and while Nokia has a powerful brand, it often has little or no information on the end-users of its handsets. Nokia, as many of its peers, outsources the actual manufacturing of its products.

The heart of Nokia’s participation in the total customer offering is the interfaces, in the form of mobile handsets. Both content and services are important parts of the total customer offering, and it works hard to make it easier for its partners to deliver these. It understands that the better the total offering, the bigger the space will become, and it will benefit along with all of its partners in providing the total customer offering. Nokia has also established “Club Nokia” in 26 countries, in which it provides services such as customer support, games, and ring tones exclusively to Nokia handset owners. The strategic benefit of this initiative is in fact at least as much in establishing direct relationships with the owners of its handset as in service provision.

The idea of a firm’s distinctive competences and strengths of course has been central to business strategy for over a decade now. In defining a company’s current strategic space, in most cases the existing understanding of the firm’s competences will be adequate, though this may be reframed in the process of redefining the space. Nokia’s core competences and strengths can be considered to be telecommunications expertise, brand and market presence, global presence and scale, and its relationships with telecoms firms.

2. Redefine your space

Having defined the strategic space in which you are currently participating, you can now begin to redefine that space. Selected strategic questions to reconceive your space, and your position within it, are shown in Table 7-3. The creative scope and active challenging of assumptions required by this phase means that highly participative—and provocative—approaches are often useful.

STRATEGIC QUESTIONS FOR POSITIONING IN THE FLOW ECONOMY – II

Redefine your space

• How is the flow of all information and value changing in relation to your current and potential customers, suppliers, and competitors?

• How can you reframe the total customer offering?

• How are market dynamics changing within each of the flow elements?

• Are there flow elements in which you do not participate that influence your ability to extract value?

• How can you leverage your existing strengths in the flow economy into new sources of revenue or value?

Table 7-3: Strategic questions for redefining your space in the flow economy

A very valuable early exercise is simply mapping the current flows of information and value within your strategic space. This can help to uncover new ways to participate in existing flows, and elucidate how they are changing, particularly from the perspective of your current and potential customers. Formal processes, such as Verna Allee’s approaches and tools for mapping value networks, can be very useful. Understanding the current status of each of the flow elements provides a foundation for identifying potential strategic moves for your company.

American Airlines was a very early leader in redefining its participation in the emerging information flows in the economy. Starting in 1959, working with IBM, it established the Sabre airline information and reservations system, which at one stage was the largest private real-time computer network in the world. In the 1990s Sabre generated more profits than its parent, playing a dominant role in one of the most information-intensive industries in the world. Now one of six global computer reservation systems, Sabre is continuing to reposition itself, having taken a 70% stake in Internet travel agency Travelocity and providing software to other airlines on an applications service provider (ASP) model.

Another example is provided by how corporate banking is redefining its scope. The family tree of JP Morgan Chase is long and distinguished one, bringing together a multitude of firms such as Manufacturer’s Hanover, Chemical Bank, and of course John Pierpont Morgan’s eponymous institution, all of which have provided financial services to the corporations of America and the world since the 19th century. JP Morgan Chase no longer provides just financial services to its traditional client base, but is now seeking to take a commanding position in the information and value flows between corporations.

Electronic Invoice Presentment and Processing (EIPP) is a digitally-based process by which firms present invoices and make payments in business-to-business transactions. At its most basic, the field is about providing electronic notifications to suppliers and clients of order status, and making the related payments. However to implement these systems effectively when there are a multitude of complex processes including internal approvals, partial shipments, returns, insurance, and far more, ultimately requires integrating the accounts payable and accounts receivable systems of the firms involved. For consumer goods companies, these systems can extend as far as providing accounting systems and payment options to retailers, while for other large firms, they can cover all aspects of procurement, including integration into online marketplaces. This emerging space is attracting competitors from all fronts, including software vendors such as SAP, start-ups such as Billpoint, and banks like JP Morgan Chase. The only part of the EIPP suite of services traditionally provided by banks is payments—a very low-margin and commoditized business. However JP Morgan Chase has redefined the scope of its business to encompass a far larger proportion of customer value.

3. Reposition

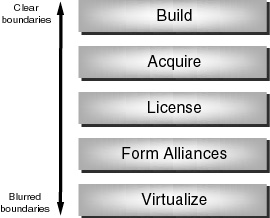

Once you have determined your new strategic space, you need to decide how you will reposition your company. You have the usual range of strategic options available, as illustrated in Figure 7-2. You can:

• Build. Create the capabilities you require, by internal development and hiring.

• Acquire. Identify and merge with a firm with complementary capabilities and positioning.

• License. Implement technologies or processes others have developed.

• Form Alliances. Create shared business models with other organizations.

• Virtualize. Outsource business processes and functions.

Figure 7-2: Strategic options for repositioning

Traditional approaches to corporate strategy remain useful in assessing this range of options. Depending on the specific situation, some of the issues to be taken into account include the degree of integration required, financing costs, the importance of market dominance, intellectual property, cultural fit, industry barriers to entry, and so on.

At the same time, it’s important to understand how the rapidly shifting dynamics of the flow economy change repositioning decisions. As you saw earlier in this book, companies can now easily integrate their processes and operations to a far deeper degree. This means that it is increasingly possible and relevant to shift towards options that require blurring the boundaries of the organization. You are severely limited in what you can achieve if you simply buy or build capabilities internally. Those firms that actively engage in the more challenging approaches of drawing on external intellectual property, forming alliances, and allocating business processes inside and outside the organization, will have immensely greater flexibility in their strategic positioning. In Chapter 3 you saw that companies today participate in a broad network of value creation, and position themselves to extract value from that. The greater your versatility in fine-tuning your positioning relative to other firms, the more accurately you can conceive and implement your strategic vision.

Lonely Planet, discussed at the beginning of this section, clearly started with its primary strength in content creation, combined with a strong brand. In seeking to develop direct relationships with its end-customers—which most book publishers don’t have—it chose to develop its own capabilities for the Internet and online community development. However for its other new ventures it has formed alliances with a telecommunication provider, television program producer, software developer, and personal organizer makers to leverage its content and brand. In all cases it ensures that it controls the customer relationships—and thus the majority of the value creation.

Microsoft has never hidden the fact that its Xbox game console is in part the first step of a strategy to be at the heart of all home entertainment. As such it needed to create a standard. It could have done that through alliances with established players, but it decided that it wanted to completely control this business. Despite being historically a software firm rather than hardware vendor, it was easy for it to outsource manufacturing of the console. However for a game console to be massively successful it needs a large range of quality games to be available, so in addition to providing its own games, it allies with third-party game developers.

Strategy in the flow economy is also about positioning relative to your competitors. Microsoft is a powerful player in many of the flow elements, however one of the elements at which it is currently weakest is connectivity. It’s happy if the market is open and competitive, but if there is a dominant player, especially combined with relationships with end-players, it could throw a wrench into its plans. So, when AT&T’s cable television business was auctioned in late 2001, Microsoft was desperate for it not to fall into the hands of its arch-rival AOL Time Warner, as it would have doubled the firm’s broadband reach to 26 million subscribers. Accordingly, Microsoft chose to bankroll Comcast’s bid for the cable networks, thus averting the powerful hold its competitor may have gained on customers’ access to digital broadband services.