Predictable pandemics and unpredictable demographics: the impact of COVID-19 and beyond

At this point COVID-19 is easily the worst pandemic since the Hong Kong Influenza (H3N2) in 1968 and the 1957 Asian flu (H2N2), both of which are estimated to have killed at least one million people, far worse than the more recent SARS, MERS, Ebola, or avian flu.

An inevitable pandemic

Some people seem to think this has come out of the blue, but a pandemic of this nature has been long anticipated by experts. Despite Goldman Sachs and Sequoia Capital among others calling the spread of coronavirus a ‘Black Swan’ event, it is absolutely not, as well-explained by the Red Team Analysis Society

I certainly do not pretend to be an expert on infectious diseases, so I have always deferred to those who are, Among a multitude of possible references, it’s easiest to draw on WHO’s recent Global Influenza Strategy 2019-2030, which states simply:

“Although it is impossible to predict when the next pandemic might occur, its occurrence is considered inevitable.”

As many health experts and the World Bank have long pointed out, the impact of a powerful infectious disease when it emerges is largely shaped by the preparedness and response of governments and health systems. Many nations’ lack of readiness was clear beforehand and has become even more obvious in recent weeks.

Increasing life expectancy defines human progress

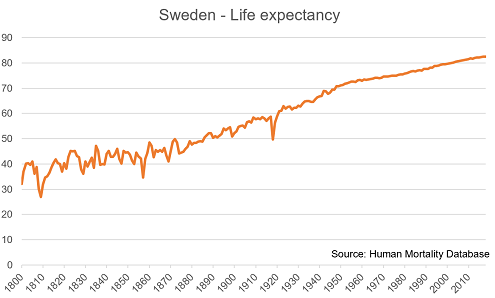

Humankind’s progress is perhaps best summarized in the consistent growth of our life expectancy of close to two years every decade for the last two centuries, illustrated by this data from Sweden, as one of the countries in the world with the longest-standing life expectancy records. There are two important insights you can quickly glean from a glance at this chart.

Humankind’s progress is perhaps best summarized in the consistent growth of our life expectancy of close to two years every decade for the last two centuries, illustrated by this data from Sweden, as one of the countries in the world with the longest-standing life expectancy records. There are two important insights you can quickly glean from a glance at this chart.

The first is that life expectancy has increased substantially since the first decades of the nineteenth century. In the 160 years before 2016 life expectancy increased from 42 to 82, so every decade life expectancy has increased by around 2.5 years.

The second is that until around 1880 life expectancy was highly volatile, impacted by both widespread diseases and wars. Since then the increase has been consistent, with in the case of Sweden little involvement in wars or exposure to pandemics.

These advances have been the result of the development of modern healthcare, which has had continued extraordinary progress since it finally became an empirical science in the nineteenth century.

Life expectancy growth flattens

Of course the life expectancy of many other nations has been far less smooth. In fact life expectancy in some developed nations has fallen recently, notably in the U.S., which due to factors including increased obesity, an opioid epidemic, and suicide, now has the lowest life expectancy of high income developed countries.

In other countries the pace of increase of life expectancy has slowed, in some cases due to similar factors. Influenza has had an impact in some countries, with reduced life expectancy in 2015 in some European countries attributed to a severe ‘flu season.

In other countries the pace of increase of life expectancy has slowed, in some cases due to similar factors. Influenza has had an impact in some countries, with reduced life expectancy in 2015 in some European countries attributed to a severe ‘flu season.

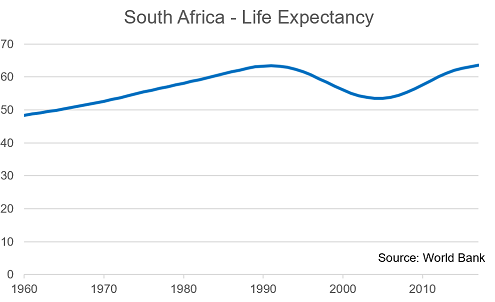

Over the last decades the life expectancy in many African countries has been dramatically hit by AIDS, illustrated by the situation in South Africa. Few people who live in the West realize the scope of the tragedy across southern Africa in this period, with youths impacted most by the disease, resulting in a massive social and economic impact. In this case epidemics have substantially impacted not just life expectancy, but the entire structure of society.

Uncertainties in our future life expectancy

One of the things we pretend to know the most about in coming decades is our demographics. Predictions of fertility rates, death rates, and migration give us specific numbers for future population figures. These often hide the uncertainties underlying the forecasts, so many people take them as given, though I am dubious about, for example, the assumptions behind the widely quoted United Nations population forecasts to 2100.

Within nations, fertility rate appears to be relatively consistent. There are no high income countries that have a replacement fertility rate, so either their populations are declining, for example Japan and South Korea, or migration is compensating for insufficient fertility, as in many Western European countries. Fertility rates are falling at a decent clip in South Asia and Africa, though how fast this will progress is significantly uncertain.

As I always point out when I speak about the future of demographics, the biggest uncertainty is in our life expectancy. On the one hand, the science of life extension, while it encompasses research of widely varying degrees of credibility, could plausibly result in substantial breakthroughs in addressing the biological mechanisms of ageing.

If this happens, the biggest uncertainty will be whether these treatments are broadly available, or only to a relatively few wealthy people. In the former case, we could see that life expectancy grows at an even faster pace than it has in the past.

Factors that could decrease our life expectancy include most notably the potential for pandemics. The 1918 Spanish flu reduced U.S. life expectancy by 12 years. Since then in the West life expectancy has not been significantly impacted by epidemics, and we have grown to trust the ability of our healthcare systems to cope with the spread of diseases.

The potential impact on demographics of COVID-19

At this point any estimation of the impact and mortality of COVID-19 is extremely speculative. It is plausible that the disease will be contained in the fairly near future, with the incidence of new cases beginning to reduce soon as nations step up their efforts, and in time treatments are developed. It is also possible that the impact will be dramatic, amplified by our deeply interconnected world, though for many reasons it is very unlikely to have anything like the mortality of the Spanish flu, given our medical capabilities and far better healthcare.

A distinguishing feature of COVID-19 is that it predominantly impacts the old, with very little effect on children and young adults. In contrast, the Spanish flu and AIDS mainly affected people of working age.

It looks likely that hard-hit countries such as China, South Korea, and Italy will report lower life expectancy for this year. The age-skewed mortality could affect demographic composition to some degree. Italy and South Korea in particular have some of the lowest birth rates in the world, and thus fastest-ageing populations. Their very top-heavy demographic profiles could shift somewhat.

Future pandemics?

Needless to say COVID-19 is a wake-up call which will not soon be forgotten. Health experts have long clamoured for better preparedness for events of this nature. There is certainly still the potential for further, potentially considerably worse, pandemics. However governments’ recognition that these are real and not imaginary threats will mean our responses are likely to be far better.

At this point we can have good hope that any negative impact on life expectancy from this coronavirus will be limited, and the demographic profiles of nations will not shift significantly. But that possibility remains. We must consider pandemics as an important possible factor shaping our future as a society.