As more jobs are automated, how many of us will still have productive work?

There has been a lot of press the last few days about a paper The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?, published by the Oxford Martin Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology.

Almost all the coverage has been on the headline figure that 47% of US employment is at risk. However the paper provides many more interesting insights when you examine the detail.

The underlying methodology of the study included examining the categorizations developed by the US Department of Labor for its O*NET jobs service, drawing on 702 job categories.

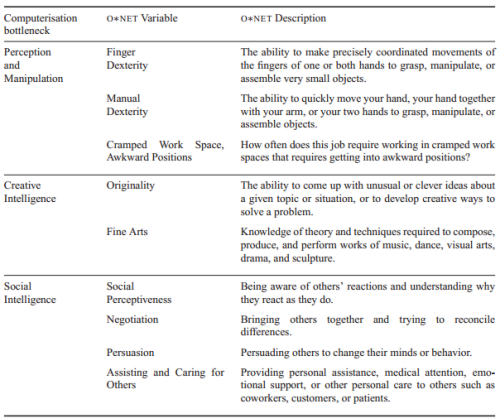

The following job characteristics in the job descriptions were assessed as less automatable.

Source: The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?

Some of these, such as Originality, Social perceptiveness, and Persuasion can certainly be recognized as being currently outside of the capabilities of computers. Manual dexterity has proven to be surprisingly difficult, though good advances are currently been made.

I would argue that Assisting and Caring for Others has a number of distinct elements, some of which may well be readily automated, and others that could be automated before many people suspect.

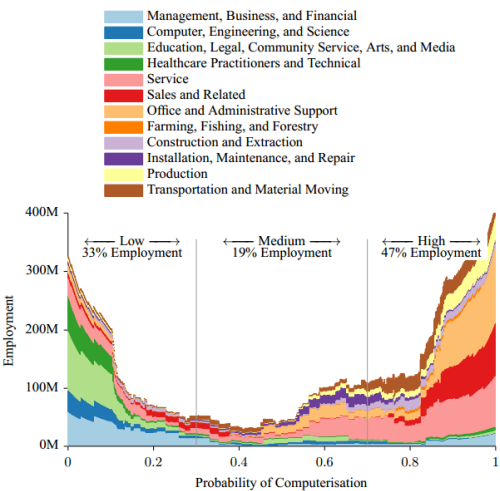

The analysis then examined the probability that each of the job roles will be automated.

Source: The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?

The area under the curve covers all US employment.

As brought out in my Future of Work framework, the forces of polarization are strongly at work, with a large majority of jobs having either a very low or very high probability of automation.

This echoes research showing that for the last three decades job growth has happened almost exclusively in low skill or high skill jobs.

The threshold of >70% probability from which the 47% of jobs figure comes from is fairly arbitrary. More meaningful is the 35% or so of jobs that have a 85% or greater chance of being automated.

Low risk job sectors include management, business, education, legal, arts, and healthcare, however even these sectors have jobs in the high-risk category.

High risk job sectors include services, sales, and office and administrative support.

The report notes that:

“Our findings suggest that recent developments in [Machine Learning] will put a substantial share of employment, across a wide range of occupations, at risk in the near future. According to our estimates, however, this wave of automation will be followed by a subsequent slowdown in computers for labour substitution, due to persisting inhibiting engineering bottlenecks to computerisation.

…

The computerisation of occupations in the medium risk category will mainly depend on perception and manipulation challenges.

…

Our model predicts that the second wave of computerisation will mainly depend on overcoming the engineering bottlenecks related to creative and social intelligence.

…

Our findings thus imply that as technology races ahead, low-skill workers will reallocate to tasks that are non-susceptible to computerisation – i.e., tasks requiring creative and social intelligence. For workers to win the race, however, they will have to acquire creative and social skills.”

Therein lies one of the most fundamental questions we face in examining the future of work:

Will everyone – or a large majority of the population – be able to develop skills that will place their work value above that of machines?

Let us do what we can, through education, inspiration, and more to get a positive answer to this question.