Futurist > Best Futurists Ever > Robert A. Heinlein

Best futurists ever: The predictions of Robert A. Heinlein, from the Cold War to the waterbed

By Martin Anderson

Among the most influential and prescient science-fiction authors of the twentieth century, Robert A. Heinlein’s contributions to culture extend from linguistics and social theory through to innovations in furniture.

His prognostications about the destiny of mankind are informed as much by our history as our potential, with a depth of understanding that makes classic novels such as Stranger In a Strange Land works of enduring world literature.

Heinlein preferred to call his output “speculative fiction.” to distinguish it from the exploitative “space opera” fare which he considered to have tarnished the SF literary genre.

Though many of his themes were broad, his interest in the technological and political future of humanity nonetheless brought up some fascinating as well as accurate predictions about the coming decades.

Nuclear arms development and the Cold War

Heinlein’s 1941 short story Solution Unsatisfactory prefigures the tension that would develop between the United States and the Communist Eastern Bloc in the decades after WWII.

This included nuclear weapons and the fear of radioactive fallout that captured popular imagination throughout the Cold War.

In particular, lethal “radioactive dust” is used in Solution Unsatisfactory by the Allies to devastate Germany and bring the Second World War to a conclusion. Yet this weapon also brought with it the understanding of a devastating technology that threatens to destabilize the world order:

Someone in the United States government had realized the terrific potentialities of uranium 235 quite early and, as far back as the summer of 1940, had rounded up every atomic research man in the country and had sworn them to silence. Atomic power, if ever developed, was planned to be a government monopoly, at least till the war was over.

It might turn out to be the most incredibly powerful explosive ever dreamed of, and it might be the source of equally incredible power. In any case, with Hitler talking about secret weapons and shouting hoarse insults at democracies, the government planned to keep any new discoveries very close to the vest.

In the story, the Department Special Defense Project No. 347 unknowingly shadows the creation and development of the top-secret Manhattan Project, the US effort to develop the first effective nuclear weapon, which would indeed conclusively end the war—though in the East, rather than the west.

Although Heinlein did not predict the explosive nature of nuclear weapons, he accurately wrote that toxic radiation would be the primary cause of death when using atomic weaponry.

Interestingly, the author gets it exactly right at one point, describing the sheer destructive scale of a nuclear device:

We had a vision of a one-ton bomb that would be a whole air raid in itself, a single explosion that would flatten out an entire industrial center.

However, Heinlein decides that the idea is too fantastical, and proceeds along the lines of a weapon that effectively uses fallout—an extension of the poison gas used to such controversial effect in the previous world war.

Heinlein also predicts the range of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), a year before the first test flight of Wernher Von Braun’s V2 rocket.

…The problem was, strangely enough, to find an explosive which would be weak enough to blow up only one county at a time, and stable enough to blow up only on request. If we could devise a really practical rocket fuel at the same time, one capable of driving a war rocket at a thousand miles an hour, or more, then we would be in a position to make most anybody say ‘uncle’ to Uncle Sam.

Solution Unsatisfactory extrapolates a timeline from the discovery of uranium fission in 1938, which led to the identification of nuclear fission the following year, and the formation of the Advisory Committee on Uranium. Knowledge about the potential of splitting the uranium atom had entered the public consciousness before security concerns around the war cast a security veil over all ongoing research.

In the story, the government envisions a global pax Americana, with the US as the trustworthy guardian of the ultimate weapon, and the ultimate deterrent to aggression:

[The weapon] is not just simply sufficient to safeguard the United States, it amounts to a loaded gun held at the head of every man, woman, and child on the globe!

But Heinlein delivers a more pragmatic view about how new military technologies develop and spread in the real world, and how the post-war arms race would actually play out in nearly a half-century in the shadow of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD):

…It’s like this: Once the secret is out-and it will be out if we ever use the stuff! — the whole world will be comparable to a room full of men, each armed with a loaded .45. They can’t get out of the room and each one is dependent on the good will of every other one to stay alive. All offense and no defense.

Computer Aided Design (CAD)

Heinlein also showed foresight into the world of design. In his 1957 novel The Door Into Summer, he prefigured the advent of the early Computer Aided Design (CAD) systems of the 1960s, which ultimately developed into modern architectural and 3D design software.

In the book, an inventor takes architectural drafting out of its traditional artisanal niche and into its ultimate logical space—numerically precise, computer-driven plotting:

This gismo [SIC] would let them sit down in a big easy chair and tap keys and have the picture unfold on an easel above the keyboard. Depress three keys simultaneously and have a horizontal line appear just where you want it; depress another key and you fillet it in with a vertical line; depress two keys and then two more in succession and draw a line at an exact slant.

Cripes, for a small additional cost as an accessory, I could add a second easel, let an architect design in isometric (the only easy way to design), and have the second picture come out in perfect perspective rendering without his even looking at it. Why, I could even set the thing to pull floor plans and elevations right out of the isometric.

The first recognizable CAD program emerged six years later in the PhD thesis work of MIT scholar Ivan Sutherland.Entitled Sketchpad, the system pioneered the idea of “instances” from template objects, now common in 3D and CAD software, where changing the original object passes those changes on to all the “live” copies.

The program was punched into tape and fed into a computer occupying 1,000 square feet and boasting 320 kb of memory, which in itself took up a cubic yard of space. You can see the system in action, including the then-revolutionary use of a touchscreen via a light pen, here.

Voice recognition technologies

The Door Into Summer also cautiously mooted the possibility of natural language recognition and speech-to-text technologies, anticipating the difficulties involved in computer-driven transcription:

[I] had expected that there would be automatic secretaries in use — I mean a machine you could dictate to and get back a business letter, spelling, punctuation, and format all perfect, without a human being in the sequence. But there weren’t any. Oh, somebody had invented a machine which could type, but it was suited only to a phonetic language like Esperanto and was useless in a language in which you could say: ‘Though the tough cough and hiccough plough him through.’

Though Bell Labs’ Audrey prototype speech recognition experiment pre-dated the novel by five years, it required a far greater amount of subject-specific training than the few minutes most iPhone users spend calibrating Siri, and could only recognize spoken numbers between zero to nine.

The Shoebox speech recognition system that IBM displayed a decade later at the World’s Fair added operators such as “”minus” and ‘plus’ to extend this vocabulary to 16 maths-related words to create a rudimentary speech-driven calculator.

The first functional speech recognition system emerged with Carnegie Mellon’s Harpy project in 1976, developed with support from The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Harpy was capable of recognising more than 1,000 words, about equivalent to the vocabulary of a three-year-old.

The Internet

Visionary science-fiction writers have been predicting a global information network since before there was any basis to make that imaginative leap.

Amongst others, Mark Twain envisaged a machine that could connect the world in a short story from 1898; E.M. Forster described a worldwide messaging and video conferencing system in 1909; sci-fi legend Isaac Asimov wrote of “computer outlets” hooked up to enormous libraries of global knowledge; and contemporary writer William Gibson anticipated the internet by eight years in the short story Burning Chrome in 1982, and at greater length in Neuromancer in 1984.

In the posthumously-published novel For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, written in 1938, Heinlein imagines a national information network. However, it’s an analog solution: a vast lattice of pneumatic tubes threading the country, through which one can send requests to librarians for photocopies of articles. As a network solution, it’s closer to the administrative tubes of the Ministry of Truth in Orwell’s 1984.

The author returned to the idea with far greater authenticity in 1983 with the novel Friday, where he gives an account of the random nature of link-exploration that is far nearer to how we currently use the Internet than the more abstract accounts in Neuromancer and similar fiction of the period.

The central character in the book describes herself as The World’s Greatest Authority, a moniker borrowed from the late US comedian Irwin Corey. At one point she describes the startlingly Google-like process of how she stumbled across his work:

At one time there really was a man known as ‘the World’s Greatest Authority.’ I ran across him in trying to nail down one of the many silly questions that kept coming at me from odd sources. Like this: Set your terminal to “research.” Punch parameters in succession “North American culture,” “English-speaking,” “mid-twentieth century,” “comedians,” “the World’s Greatest Authority.” The answer you can expect is “Professor Irwin Corey.” You’ll find his routines timeless humor.

Sensor-driven lights

We’re becoming increasingly used to lights that turn themselves on or off when we enter or leave a room. Since they’re usually activated by movement, it’s not yet a perfect solution. In the 1950 novella The Man Who Sold The Moon, Robert A. Heinlein envisages a better approach”

As they left their joint office, Strong, always penny conscious, was careful to switch off the light. Harriman had seen him do so a thousand times; this time he commented. ‘George, how about a light switch that turns off automatically when you leave a room?’

‘Hmm—but suppose someone were left in the room?’

‘Well. . . hitch it to stay on only when someone was in the room—key the switch to the human body’s heat radiation, maybe.’

At present the heat-sensing light-switch is not a mainstream consumer product, though Passive infrared (PIR) sensors are gaining commercial ground.

The waterbed

Heinlein’s 1961 bestselling novel Stranger In A Strange Land is perhaps his best-known work, and his most influential.

The US Library of Congress numbers it among the 88 books that shaped America; it contributed a new word— ‘grok’ permanently to English literature, and to computer culture; it even created an enduring new church movement centered around the core themes and ideas of the novel.

Yet the only distinct technological prediction that emerged from it was the curious idea of the waterbed—now considered one of the oddest crazes of the 1970s.

Heinlein had first described a waterbed in his 1942 novel Beyond This Horizon, and then in the Hugo award-winning Double Star in 1956:

Against one bulkhead and flat to it were two bunks, or “cider presses”, the bathtub-shaped hydraulic, pressure-distribution tanks used for high acceleration in torchships…

Two gravities is not bad, not when you are floating in a liquid bed. The skin over the top of the cider press pushed up around me, supporting me inch by inch; I simply felt heavy and found it hard to breathe.

The waterbed in Stranger In A Strange Land likewise has therapeutic properties:

This young man Smith was busy at that moment just staying alive. His body, unbearably compressed and weakened by the strange shape of space in this unbelievable place was at last somewhat relieved by the softness of the nest in which these others had placed him…

The patient floated in the flexible skin of the hydraulic bed. He appeared to be dead.

The origin of this fascination was Heinlein’s own experience as a bedridden convalescent after being discharged from the US Navy in 1934 for tuberculosis. In Expanded Universe (1980), he describes how the idea occurred:

I designed the waterbed during years as a bed patient in the middle thirties; a pump to control water level, side supports to permit one to float rather than simply lying on a not very soft water filled mattress. Thermostatic control of temperature, safety interfaces to avoid all possibility of electric shock, waterproof box to make a leak no more important than a leaky hot water bottle rather than a domestic disaster, calculation of floor loads (important!), internal rubber mattress and lighting, reading, and eating arrangements—an attempt to design the perfect hospital bed by one who had spent too damn much time in hospital beds.

Heinlein’s descriptions over the three novels were so detailed as to defeat US entrepreneur Charles Hall, who wanted to patent the idea in the 1960s. Ultimately Hall was able to begin manufacturing, and is currently attempting to interest millennials in a waterbed revival.

A legacy of the future

Heinlein’s predictions combine a broad visionary streak with an inventor’s practical curiosity. Though he wrote about the spiritual destiny of our species, much of his most accurate foreshadowing arose from inconveniences that he experienced in his own life. As we’ve seen, several of his predictions are still maturing.

With a varied and evolving output that would divide his fans throughout his career, Heinlein never achieved stable and consistent recognition either during his lifetime or posthumously. His prose and ideas lacked the signature stylistic and thematic hallmarks that were to distinguish peers such as Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and Isaac Asimov. But this intellectual restlessness may have contributed to his above-average ability to predict the technology of our times.

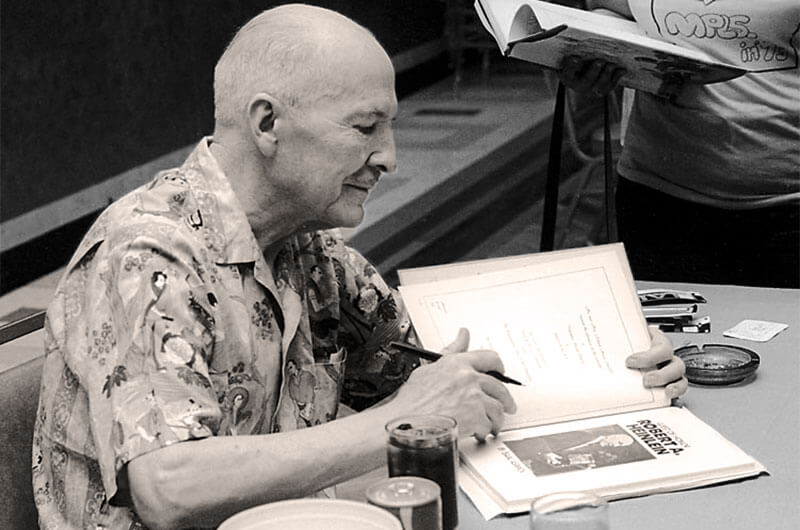

Image sources: Dd-b/WikiMedia Commons