Futurist > Best Futurists Ever > William Gibson

Best futurists ever: How William Gibson’s Neuromancer shaped our vision of technology

By Matthew Kennedy

“The future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.” —William Gibson

Despite the misleading title of the genre, speculative fiction isn’t about the future—it’s about the present. It offers glimpses into hypothetical realities and futures, in which things are often extrapolated to their logical conclusion, in order to help us reflect on the “now.”

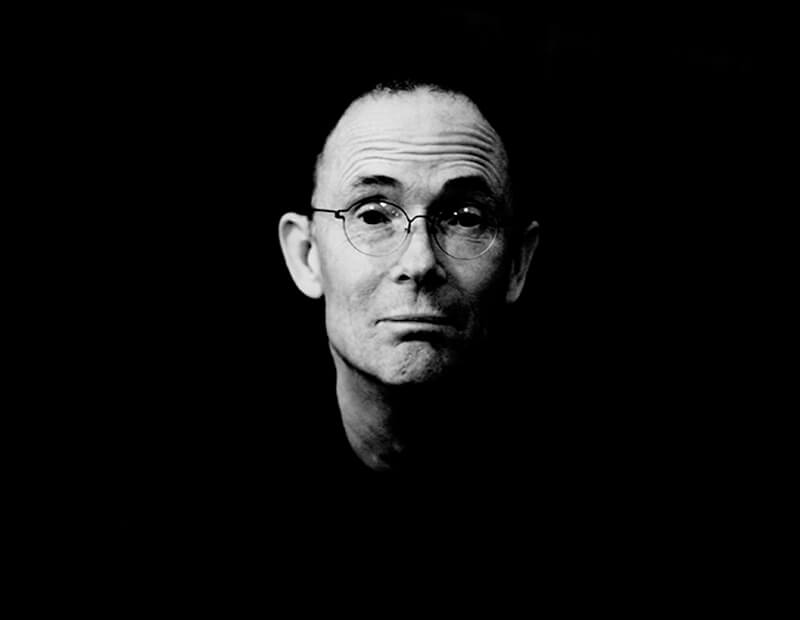

William Gibson is a master of this craft. He’s the author of more than 10 novels, including the landmark work Neuromancer (1984) and—most recently—The Peripheral (2014). Over the course of his career, Gibson has made an indelible contribution to literature, culture, and even our conceptions of and interactions with technology.

It’s worth noting that Gibson has never claimed to predict the future. Indeed, read any interview with the author—such as this one with The Paris Review—and you’ll notice that he explicitly denies any charges of prescience.

However, there is a wealth of forethought in his work. Gibson has an unmatched knack for analyzing trends and behaviors inherent to modern life and extrapolating them into vivid themes that reveal a kind of raw truth about humanity—much of which centers on our relationship with technology.

For Gibson, it’s not about how technologies work, it’s about what they do to us.

Below, we explore a handful of ideas from his seminal novel Neuromancer and their influence on contemporary culture.

The Internet and its ubiquity

In 1984, five years before Tim Berners-Lee introduced the Internet to the world (and six years prior to the first web browser), Gibson coined the term “cyberspace”—his version of the World Wide Web. It first appeared in a short story title Burning Chrome (1982). Two years later, it was popularized by his debut novel, Neuromancer:

“Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts… A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding…”

The concept of the Internet precedes Gibson’s work; whether he knew of its existence when he wrote his first novel is unclear, but Gibson says his inspiration for cyberspace came from arcades:

“…I was looking into one of the video arcades. I could see in the physical intensity of their postures how rapt the kids inside were…These kids clearly believed in the space games projected…” —William Gibson, Conversations with William Gibson

Gibson’s evocation of a virtual world in Neuromancer wasn’t technologically accurate, but it’s depiction of its ubiquity certainly was.

Furthermore, the gritty aesthetic and darkly comic feel of the novel helped to solidify a burgeoning genre known as cyberpunk, which would forever change science fiction.

Our dependence on technology

The novel’s depiction of humanity’s utter reliance on and obsession with technology was all too prescient. Thirty-three years after its publication, Neuromancer’s portrayal of technological dependence is somewhat analogous to people’s dependence on computers, smartphones, and the Internet today.

But Gibson took that dependence to its extreme, as demonstrated by Neuromancer’s protagonist, Case, and his addiction to cyberspace:

“A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he cut in Night City, and he’d still see the matrix in his dreams, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colourless void… The Sprawl was a long, strange way home now over the Pacific, and he was no Console Man, no cyberspace cowboy. Just another hustler, trying to make it through. But the dreams came on in the Japanese night like livewire voodoo, and he’d cry for it, cry in his sleep, and wake alone in the dark, curled in his capsule in some coffin hotel, hands clawed into the bedslab, temper foam bunched between his fingers, trying to reach the console that wasn’t there.”

Augmented reality

Gibson didn’t just predict the Internet, he also wrote about augmented reality (AR) prior to its inception.

In the novel, the protagonist, Case, uses a “deck,” goggles and electrodes to connect with cyberspace—a degree of connectivity that hasn’t come to fruition. However, another character, Molly Millions, wears surgically attached glasses that augment her vision:

“He realized that the glasses were surgically inset, sealing her sockets. The silver lenses seemed to grow from smooth pale skin above her cheekbones…” —William Gibson, Neuromancer

Of course, surgically attached glasses are far from mainstream, but notionally Gibson was right on the money. This is evident in the advent of AR devices such as Google Glass, Microsoft HoloLens, and others—none of which are ubiquitous (yet), but might be someday (once someone designs an aesthetically pleasing model).

Corporate hegemony and globalization

Gibson has explored themes of corporate power and control in a number of his novels, including in Neuromancer:

“Power, in Case’s world, meant corporate power. The zaibatsus, the multinationals that shaped the course of human history, had transcended old barriers. Viewed as organisms, they had attained a kind of immortality. You couldn’t kill a zaibatsu by assassinating a dozen key executives; there were others waiting to step up the ladder, assume the vacated position, access the vast banks of corporate memory…”

What may have been a reflection on the escalating corporate greed associated with the 1980s is all the more relevant in the present, with legislation—such as SOPA and DMCA—being created by industry lobbies to protect corporate interests on a global scale.

In a 2007 interview with Reuters, Gibson expounded on this topic:

“I don’t think globalization existed as a concept in 1981 but ‘Neuromancer’ is set in a very nasty globalized society in which there does not seem to be any surviving middle class. There are only millionaires and people on the street—like in Moscow and some of the other less fortunate parts of the world. Everyone says I foresaw cyberspace but I did foresee the world of globalization.”

Indeed he did. He also foresaw, and shaped, a great deal more than that.

Stay tuned for more on William Gibson—we’ll be delving into other intriguing insights from his diverse and highly influential body of work.

In the meantime, we recommend Gibson’s 2014 interview with Chicago Humanities Festival to get further insights from his unique perspectives.

Image sources: Frederic Poirot