Futurist > Best Futurists Ever > Arthur C. Clarke

Best futurists ever: The big hits and the misses from Arthur C. Clarke’s eccentric and influential predictions

By Martin Anderson

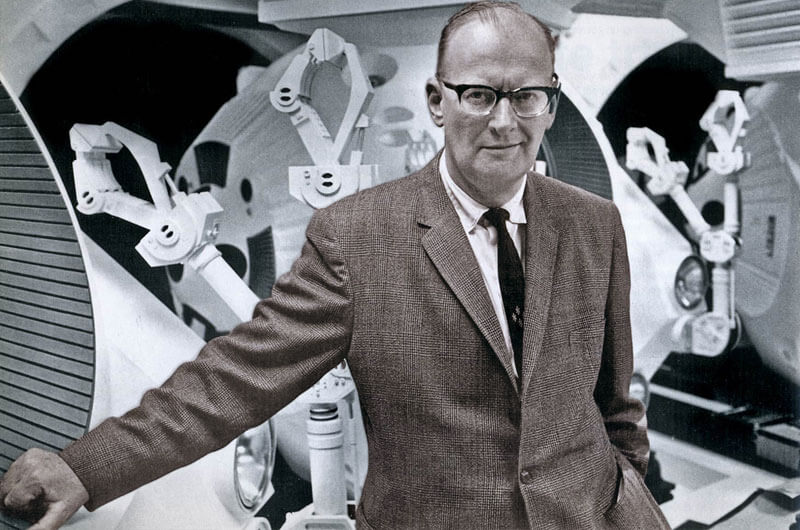

By the time acclaimed director Stanley Kubrick picked Arthur C. Clarke out from contemporaries such as A.E. Van Vogt and Robert Heinlein to collaborate on the ground-breaking 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) in 1964, the English science fiction author was already perhaps the most influential futurist of the 20th century. He was certainly the most famous.

For over sixty years Clarke produced ‘hard’ sci-fi novels and short stories that balanced a fertile speculative imagination with a characteristic scientific rigor. His work was informed by his background in mathematics and physics, and enriched by his professional association with the telecommunications and space industries of his era.

The cultural impact of 2001 would seal his position as the go-to authority on the future until his death in 2008. However, his prophecies were products of a more optimistic time — perhaps one reason for their enduring appeal.

He was never reluctant to speculate, and the sheer volume of his predictions included some noteworthy eccentricities — as we’ll see shortly.

1: Communications satellites

Prior to his two-year presidency of the British Interplanetary Society from 1946, Clarke wrote a famous essay in Wireless World, suggesting the possibility of re-using Nazi V2 rocket technology to place satellites in a geostationary orbit around the earth in order to create a global relay network.

An “artificial satellite” at the correct distance from the earth would make one revolution every 24 hours; i.e., it would remain stationary above the same spot and would be within optical range of nearly half the earth’s surface. Three repeater stations, 120 degrees apart in the correct orbit, could give television and microwave coverage to the entire planet.

The Wireless World letter earned Clarke general recognition as the originator of the idea of the geosynchronous satellite, which now officially occupied a ‘Clarke orbit’. Later, the author modestly described his inspiration for geostationary orbit as ‘the only original idea of my life’.

However the concept builds on earlier calculations and theorems by Russian scientist and mathematician Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Tsiolkovsky, like Clarke, was a scientist whose passions extended into the writing of visionary science-fiction. It was he who first calculated the 8 km per second velocity necessary to escape the earth’s orbit. He also anticipated the multi-stage boosters likely to be necessary to achieve this, as Clarke describes in his 1945 letter.

2: Remote surgery

In the 1975 novel Imperial Earth, Clarke describes how serious a problem an unreliable or ‘laggy’ network connection can be, when the data being delayed is the movement of a surgeon’s hands to control a robot that’s performing an operation:

“Hawaii’s almost exactly on the other side of the world–which means you have to work through two comsats in series. During tele-surgery, that extra time delay can be critical.” So even on Earth, thought Duncan, the slowness of radio waves can be a problem. A half-second lag would not matter in conversation; but between a surgeon’s hand and eye, it might be fatal.

In this novel, Clarke developed a prediction he had made publicly in 1964:

I’m perfectly serious when I suggest that one day we may have brain surgeons in Edinburgh operating on patients in New Zealand.

The author was entirely correct to predict that network issues would hamper the progress of remote surgery. It’s estimated that connection latency for tele-surgery needs to be no higher than 1ms — a very ambitious target, even with new 5G networks, and special compression methods to transmit haptic data (touch-based feedback for surgeons).

In February 2015 an experimental cardiac telesurgery was hampered by such communications glitches, including low voice quality between the on-site team and the remote surgeon, and poor dexterity from the surgical robot. The details of the incident came to light in an inquiry in November of 2018.

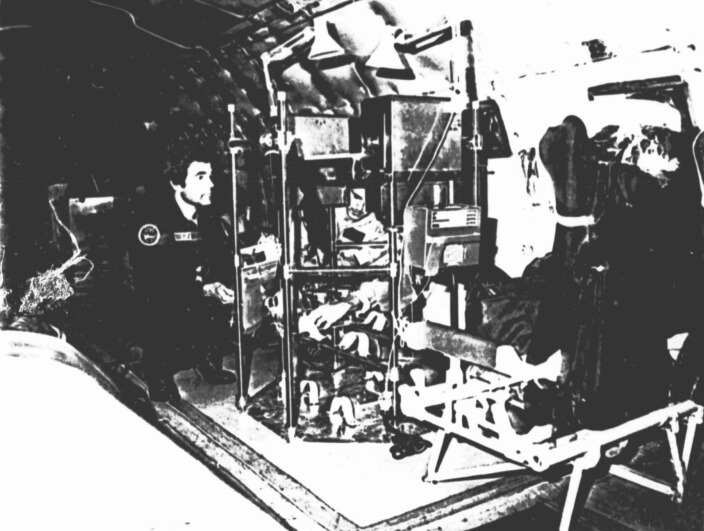

The use of remote surgeons had interested NASA since the 1970s, because of the potential to treat serious injuries in space missions where no medical doctors might be present. By the early 1980s the first concrete proposals had emerged, culminating in current efforts to develop robot-assisted surgical technologies for potential manned Mars-flights.

The first known use of robotic surgery occurred over twenty years after Clarke’s initial prediction, when the PUMA 560 C inserted a needle into a patient’s brain for a biopsy.

In 2001, a French-Canadian medical team pioneered a remote gallbladder removal, with the surgeon operating from New York on a patient in France. The endeavor was named ‘The Lindbergh Operation’, in honor of Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic crossing in 1927.

Image: Zero gravity surgery module, NASA

3: The internet

In an interview with Australian TV in 1974, Clarke was asked by a reporter what the world of 2001 would look like for his own young son by the year 2001.

He will have in his own house [a console] through which he can talk to his friendly local computer and get all the information he needs for his everyday life; his bank statements, his theater reservations…all the information you need in the course of living in a complex modern society.

This will be in a compact form in his own house. He’ll have a [television screen] and a keyboard, and he’ll talk to the computer and get information from it. He’ll take it as much for granted as we take the telephone.

At an MIT press conference two years later, Clarke expanded on the kind of interactive technology that would enable email and other forms of network messaging that are now familiar to us:

It would be a high-definition TV screen, and a typewriter keyboard, and through this you can exchange any type of information, send messages to your friends. They can wait and when they get up they can see what messages have come in the night.

Twelve years earlier, this vision of a networked society had already taken shape in Clarke’s mind. In an interview for the BBC program Horizon in 1964, Clarke said:

[Communications satellites] will make possible a world in which we can make instant contact with each other wherever we may be. Where we can contact our friends anywhere on Earth, even if we don’t know their actual physical location. It will be possible in that age, perhaps only fifty years from now, for a man to conduct his business from Tahiti or Bali just as well as he could from London.

Imperial Earth features a device called a Comsole, a terminal to a vast repository of information, complete with its own search engine:

All the libraries and museums that had ever existed could be funneled through this screen and the millions like it scattered over the face of Earth. Even the least sensitive of men could be overwhelmed by the thought that one could operate a Comsole for a thousand life-times–and barely sample the knowledge stored within the memory banks that lay triplicated in their widely separated caverns…

4: Search engines

More specifically, Clarke’s predictions for how we would ultimately locate information were to prove far more accurate than most of his contemporaries. At the 1976 MIT conference, Clarke describes information retrieval in the future:

You can call in through [a console] any information you want: airline flights, price of things at the supermarket, books you’ve always wanted to read…

News, selectively; you can tell the machine I’m interested in such and such items, sports, politics and so forth, and the machine will go to the main central library and bring all this to you, selectively – just what you want; not all the junk that you have to get when you buy the two or three pounds of wood pulp which is the daily newspaper.

Though Clarke’s vision does not include the kind of prototype pointing devices in development at Palo Alto Research Center around this period, it is a remarkably accurate view of a modern laptop search, from an age where punch-cards still had more than a decade of life left in them.

5: Spam mail and personalized ad targeting

At one point in 1975’s Imperial Earth, a Comsole user receives one of the earliest examples of spam communications based on data mining:

“[There] are some smart operators around, on the lookout for innocents from space. Yesterday I was going through a display of Persian carpets — antique, not replicated — wondering if I could possibly afford to take a small one back to Marissa. (I can’t.) This morning there was a message — addressed to me personally, correct room number — from a dealer in Tehran, offering his wares at very special rates. He’s probably quite legitimate, and may have some bargains–but how did he know? I thought Comsole circuits were totally private. But perhaps this doesn’t apply to some commercial services. Anyway, I didn’t answer.”

Today we are all too familiar with creepily apt ads enabled by tracking technologies that use our online history to define our demographic status and target advertising campaigns at us.

6: Tablet computing device and interface

The small form factor tablet device was prefigured in a number of science fiction properties from the 1950s onwards, notably in the Star Trek TV series in development at the same time as 2001. Trek‘s Personal Access Display Device (PADD), featured in The Original Series (1966-69), was stylus-operated. Its 1980s successor went on to inspire the touch-driven interface of Apple’s iPad.

However, the Newspad from 2001: A Space Odyssey differs from both iterations of the Star Trek device in that it describes the thumbnail interfaces we are now familiar with:

One by one he would conjure up the world’s major electronic papers; he knew the codes of the more important ones by heart, and had no need to consult the list on the back of his pad. Switching to the display unit’s short-term memory, he would hold the front page while he quickly searched the headlines and noted the items that interested him.

Each had its own two-digit reference; when he punched that, the postage-stamp-sized rectangle would expand until it neatly filled the screen and he could read it with comfort. When he had finished, he would flash back to the complete page and select a new subject for detailed examination.

7: The rise of digital and network pornography

In a 1959 essay published in The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke, the author describes a real-life encounter with a U.S. network executive excited by the possibilities that satellites and new communications technologies might give rise to in the field of adult entertainment. After a number of meetings, Clarke is shown a proposed reel for transmission.

“My God!” I said, when I had recovered some of my composure. “Are you going to telecast that?”

Hartford laughed.

“Believe me,” he answered, “that’s nothing; it just happens to be the only reel I can carry around safely. We’re prepared to defend it any day on grounds of genuine art, historic interest, religious tolerance—oh, we’ve thought of all the angles. But it doesn’t really matter; no one can stop us. For the first time in history, any form of censorship’s become utterly impossible. There’s simply no way of enforcing it; the customer can get what he wants, right in his own home. Lock the door, switch on the TV set—friends and family will never know.”

In a rare note of depression, Clarke concludes that his contribution to new network communications may ‘have unwittingly triggered an avalanche that may sweep away much of Western civilization’, and laments his connection with ‘this whole sordid business’.

By 1999, the subject of digital pornography had entered Clarke’s output directly. There are references to intercepting porn in The Trigger, a novel concerned with the social impact of technology and co-written with Michael P. Kube-McDowell.

The 1988 novel Cradle, this time co-written with Gentry Lee, features a videogame (loaded from several compact discs) which contains interactive sex scenes based on popular pornographic stars.

Failure to launch: the incorrect predictions of Arthur C. Clarke

It’s a mistake to do the maths on Clarke’s prediction success rate and assume he was ‘carpet-bombing’ in the hope of getting at least a few hits. Most of his more doubtful prophecies came towards the end of his career, when he seemed to be getting more personal amusement than professional benefit from his prognostications.

These more outlandish later foretellings included: the discovery of the first human clone in 2004; the return of soil samples from Mars in 2005; the closure of the last coal mine in 2006; the destruction of all nuclear weapons in 2008; the abolition of all existing currencies in 2016; the end of professional criminals via electronic monitoring in 2009 (though this does now provide a cost-saving possibility for prison systems); the ascension of AI to ‘human level’ in 2020; genetically-cloned dinosaurs in 2023; and many other wild speculations.

Of his ‘golden age’ mis-predictions of the 1960s, two are often singled out, and both are special cases:

Simian servants

Clarke predicted in the 1964 Horizon special that bioengineering would make possible a race of slaves based on monkeys. With an amused smile, the author said:

[With] our present knowledge of animal psychology, and genetics, we could certainly solve the servant problem with the help of the monkey kingdom. Of course, eventually our super-chimpanzees would start forming trade unions, and we’d be right back where we started.

Clarke made this broadcast a year after Pierre Boule’s science-fiction novel La Planète des Singes (Monkey Planet) was published, presenting an imagined world where apes are the dominant intelligent species. This event seems, logically, to have fueled Clarke’s off-beat prediction.

The book would eventually become the hit 1968 U.S. sci-fi movie Planet Of The Apes, with later sequels that closely follow Clarke’s forecast of a monkey uprising.

Telecommuting

However, telecommuting was no joke for Clarke; his interest in using new telecommunications technology to shrink the world was both personal and visionary, a promise of general technological emancipation that formed the background of many of his other predictions.

The author’s prediction of remote surgery was part of a much wider prevision of a remote work culture that would finally discard the polluted, centralized cities of the previous 150 years:

[Men] will no longer commute – they will communicate. They won’t have to travel for business any more — they’ll only travel for pleasure. I only hope that when that day comes, and the city is abolished, the whole world isn’t turned into one giant suburb.

In reality, the more that improved broadband and other technologies have enabled telecommuting, the greater corporate resistance has grown to the trend. Companies which were once pioneers of remote work for employees have reversed their policies in the last few years, while the explosive growth in urban property prices in major cities suggests that cities are set to consolidate and grow rather than become redundant nodes in a net-driven virtual workplace.

Since decentralizing is such a radical prospect, the possible reasons for the failure of telecommuting are many: the impact that it would have on many economic areas, from transport through to hotels; the destabilization of the urban property prices that have underwritten the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis; and even just plain distrust of the remote employee.

A utopian standpoint

Well into his fifties, Clarke was already considered one of the ‘Big Three’ most influential authors of the Golden Age of science fiction (together with Isaac Asimov and Heinlein) when his association with Kubrick pushed him to the apogee of his fame.

The aspirational tone of his predictions was informed by a post-war culture which had led to new social contracts and general prosperity across the west.

Even the Cold War tensions which had arisen in the aftermath of the Second World War were now fueling Clarke’s dreams, in the form of the Space Race.

As consciousness around the Vietnam war began to give rise to a new counterculture, and to more dystopian trends in science fiction, Clarke retrenched. To the end of his career, he would maintain a positive standpoint about the potential of technology to improve the lot of mankind.

If some of these predictions (particularly around telecommuting) did not account for social or economic resistance, or for the eventual fading of the progressive post-war spirit, it’s understandable. Clarke’s generation had led the world out of darkness, and his writing was a natural evolution of the emancipated utopias envisaged by Victorian masters such as H.G. Wells. For a time, such perfected visions of humanity’s future seemed a fitting and even likely reward for the horrors of the Second World War.

His view emerged from a post-war society which, quite literally, saw no other way than ‘up’. Clarke could not predict that the economics of the 1970s would foreshorten the Apollo program, or that mankind would scale back its interest in space exploration so drastically, and for so long.

Since Clarke dealt very little in dystopias, his science fiction works were not primarily intended as warning bells for society, but rather as inspirational reflections. From that standpoint, one could argue that they served no purpose other than to amuse. Indeed, Clarke seemed to approach prophecy more as a wry marketing tool than a serious map of the future:

Trying to predict the future is a discouraging and hazardous occupation, because the prophet invariably falls between two stools:

If his predictions sound at all reasonable, you can be quite sure that in twenty or, at most, fifty years, the progress of science and technology has made him seem ridiculously conservative.

On the other hand, if, by some miracle, a prophet could describe the future exactly as it was going to take place, his predictions would sound so absurd, so far-fetched, that everybody would laugh him to scorn.

This has proved to be true in the past, and it will undoubtedly be true, even more so, of the century to come. The only thing we can be sure of about the future is that it will be absolutely fantastic.

So if what I say now seems to you to be very reasonable, then I’ll have failed completely. Only if what I tell you appears absolutely unbelievable, have we any chance of visualizing the future as it really will happen.