Why scenario thinking (more than scenario planning) is critical for executives today

I recently gave a presentation to the executive team of a major mining services company at their annual strategy offsite. As has been a frequent style of engagement for me this year, my role was to stimulate broader, longer-term thinking by talking about the future of business.

While I have been doing a range of scenario planning work recently, in this case I simply wanted to impress on the executives the importance of scenario thinking. I showed the following three slides to support my discussion of the issues.

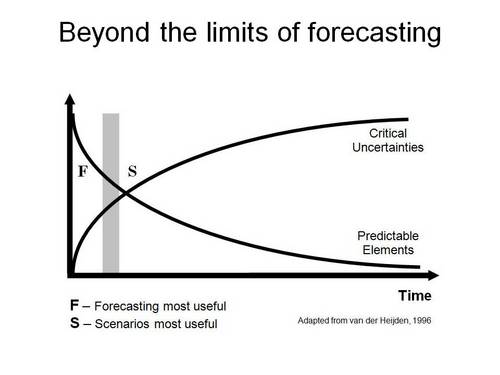

Particularly having come from a financial services background, I have seen extensive misuse of forecasts. Forecasts are only worth doing in the timeframe within which they have a reasonable chance of being accurate. Beyond that timeframe, any use of the forecasts is misleading and will lead to bad decisions. This doesn’t mean that we can’t think any further out. But taking a structured process to decision-making requires addressing the scope of uncertainty rather than taking stabs in the dark.

Scenario planning is a significant process that brings together very diverse input to create a set of scenarios that inform effective decision-making. Scenario thinking is more simply thinking about the world in terms of possibilities rather than forecasts, always understanding that ideas about where things are going can turn out to be very wrong. One of the most valuable outcomes of a well-designed scenario planning process is a shift to scenario thinking by the participating executives.

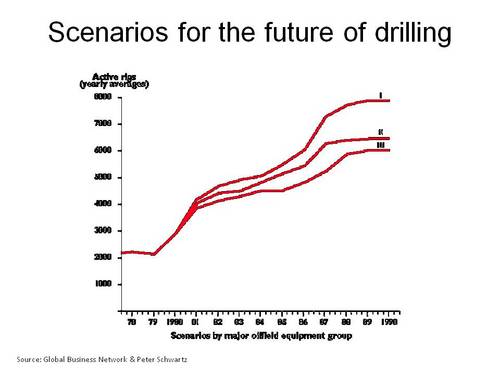

But scenario planning is not the same thing as scenario thinking. This old case study, courtesy of Peter Schwartz and Global Business Network, ably demonstrates the point.

In 1980 a major oil drilling equipment company engaged in a scenario planning project to assist their strategy development. The oil price had risen from $4 in 1970 to $50 in 1980. The boom times were at hand, and the higher price and increased investment had uncovered new oil prospects, suggesting the number of new drilling rigs could only increase. The question was by how much, as their three scenarios above suggested. It was very difficult for executives or consultants to even entertain other thinking. As Energy Bulletin notes, “forecasters who saw anything besides the accepted norm were ridiculed, especially in oil hub Houston.”

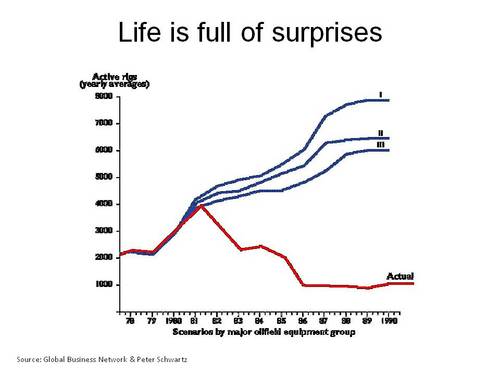

The reality proved to be very different. A combination of factors, including global recession (partly induced by high oil prices of the late 1970s), many new oil sources, and Saudi Arabia choosing to increase production by 50% for political reasons, resulted in an oil price of just over $5 by 1985. As a result, many drilling rigs were closed down as uneconomical and almost no new ones were started.

The point is that scenario planning is a process that, done ineffectively, does not challenge or change assumptions or beliefs about what is likely to happen. Scenario thinking is an entirely different matter. It is a state of mind where very different futures are seen as plausible and possible.

One of the most valuable outcomes of an effective scenario planning process is that it fosters scenario thinking among the participating executives. A good set of scenarios can be very valuable in setting strategy. However if executives are stimulated by the process to think in terms of possibilities rather than likelihoods, that can be far more powerful.

Given the increasing pace of change in most industries, the timeframe within which forecasting is useful is ever-shrinking. Building effective scenario thinking capabilities is essential for being able to build robust strategies and in all leadership development.