The Value of Collaboration: Improving Innovation in University-Business Relationships

This paper was originally published in Academic Leadership Series: Improving Innovation and Collaboration Between Industry and Business Schools, based on a keynote by Ross Dawson at CA ANZ Thought Leadership Forum.

Introduction

What is the value of academic–business collaboration? The current landscape suggests that there is much potential value that is not being realised, which begs the question, what is possible? What value can be created through utilising the wealth of resources we have in the academic–business sector, for the benefit of the business community and society more broadly?

To answer these important questions we must first understand the true value of collaboration. Collaboration is the source of new ideas – it is where innovation comes from. Collaboration makes connections between things that already exist and can be brought together. As Kary Mullis (1999), the Nobel Prize Winner for Chemistry, said about his own research: “I didn’t find anything new; I just connected things that existed before”. This is at the heart of the value creation that comes from collaboration – from being able to pull together the seemingly disconnected.

Making connections starts in our minds, but the connections take shape through many different paths, notably in conversations and in organisations, where capabilities and resources are channelled by technology and research.

The Academic World

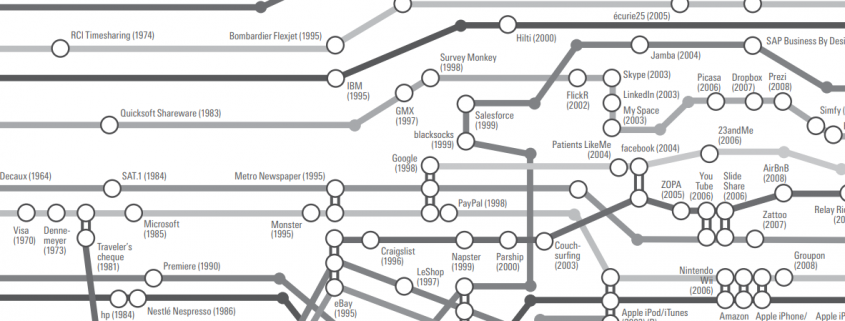

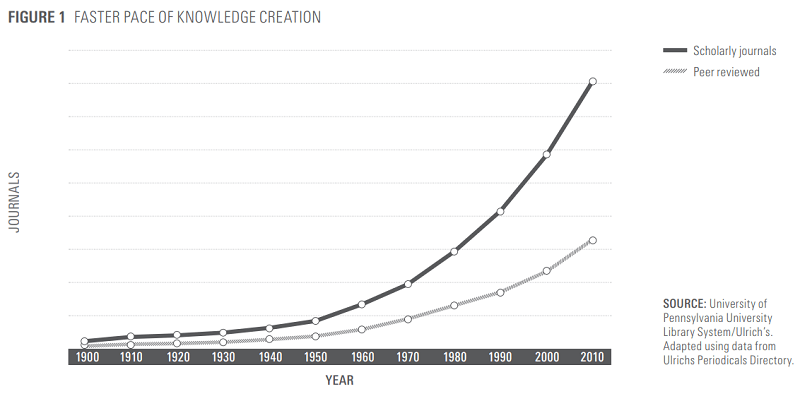

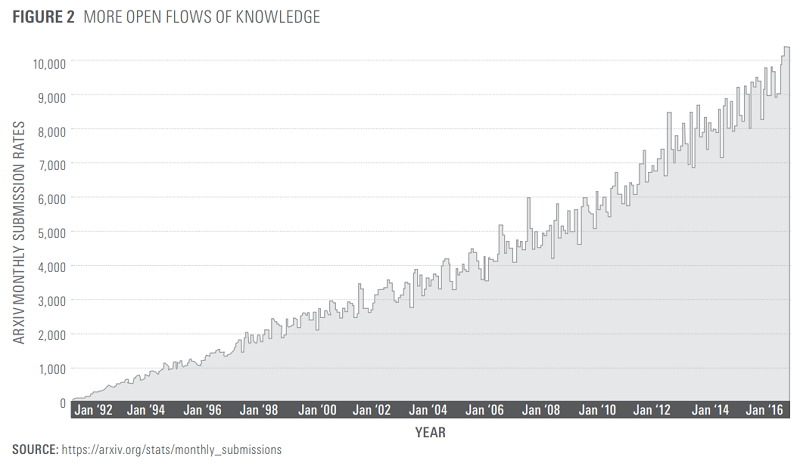

The pace of knowledge creation in academia is rising. We have evidence of this in the increase in the number of peer-reviewed articles published. Figure 1 shows the growth in scholarly and peer-reviewed journals from 1900 to 2010 and Figure 2 shows the monthly submission rates on arXiv, an open access journal. There has been increasing emphasis on openness in academic research and this shift in accessibility has the potential to be transformative. It moves research from a cumbersome process of lengthy peer review and a narrow audience to immediacy and accessibility, where new ideas can be immediately used and connected to create new possibilities. The potential of these connections are rapidly growing, requiring greater collaboration.

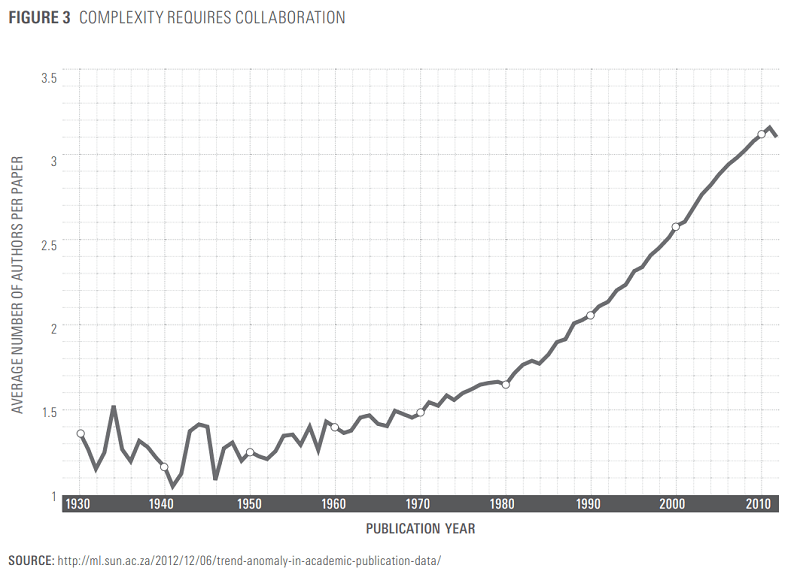

Figure 3 shows the average number of authors per paper from 1930 to 2010. It shows that in the past papers were more commonly authored by one person, however the number of authors per paper has increased significantly over the years. This increase in collaboration is driven, at least in part, by the growing complexity of the interconnected world, in which it is necessary to bring more expertise together to push out the boundaries of knowledge.

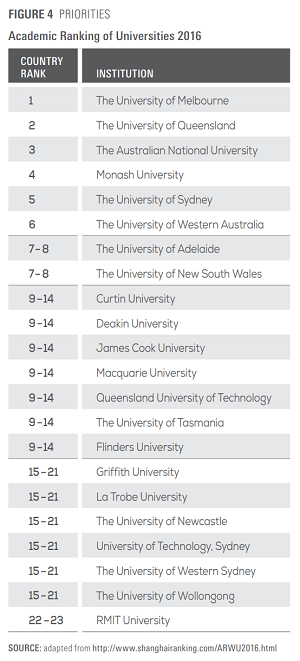

There are a range of methods for ranking academic institutions. Figure 4 shows the Shanghai ranking, which is mostly based on research publications, citations, and related factors. It demonstrates that the key to success in the academic world is in publishing – this is how institutionalised reward mechanisms are set up and how institutions themselves are ranked. University success, therefore, relies on a narrow measure, one which is contrary to facilitating collaboration. Embedded reward structures in universities do not encourage engagement and impact in the business world.

There are a range of methods for ranking academic institutions. Figure 4 shows the Shanghai ranking, which is mostly based on research publications, citations, and related factors. It demonstrates that the key to success in the academic world is in publishing – this is how institutionalised reward mechanisms are set up and how institutions themselves are ranked. University success, therefore, relies on a narrow measure, one which is contrary to facilitating collaboration. Embedded reward structures in universities do not encourage engagement and impact in the business world.

Similarly, university timeframes are not aligned with those in the business world. Businesses operate on very short timeframes while research projects take a much longer time. Another significant challenge in the academic world is the intellectual property structures of university administration – patent offices, technology transfer offices, and so on, which set boundaries on collaboration. Boundaries are everywhere in the academic world, not least in the way universities have traditionally been structured into faculties based on disciplines. This is counter to the widely recognised way forward for collaboration – multidisciplinarity. Discipline boundaries are artificial structures even in the purest academic terms but much more so when thinking about academic–business collaboration,n because every aspect of every other faculty touches business in some sense.

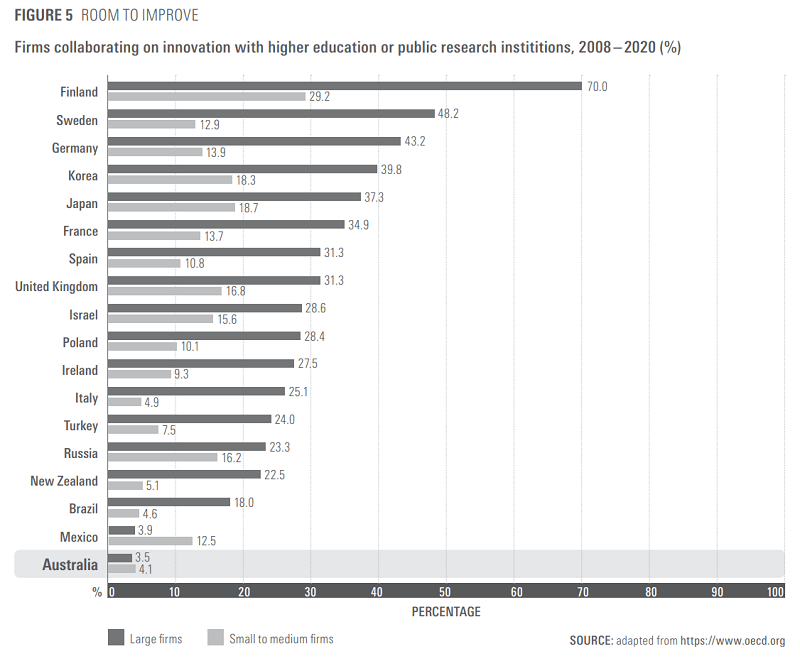

Bounded thinking also constrains academics – the concept commonly referred to as ‘the ivory tower’, in which academics consider business as someone else’s work. Academics are good at collaborating with each other (see Figure 2), but how well do they collaborate with others? Figure 5 shows the OECD ranking for firms collaborating with universities. Australia appears at the bottom of the chart.

The Business World

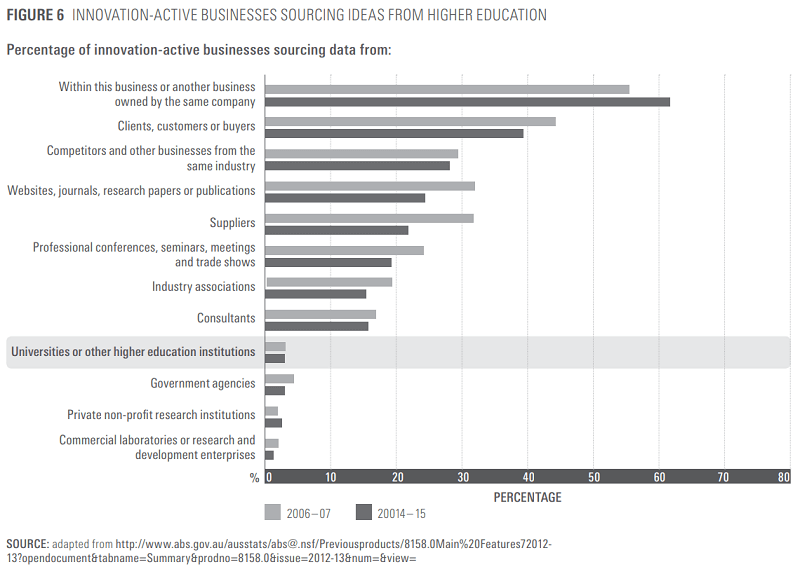

Increasingly value creation in the business sector does not happen only within organisations, but across business ecosystems. This is at the heart of how business works today, where organisations collaborate with their partners, customers, suppliers and other organisations. Business, unlike universities, is one of the most transdisciplinary domains. However, just as academics may be characterised as looking down at business from their ivory towers, business may also be perceived as thinking of academia as far removed from the reality of a world in which people ‘get their hands dirty’. Figure 6 shows the percentage of innovation active businesses sourcing ideas from universities or other higher educational institutions (DIIS/ABS). Only a small percentage of Australian businesses say that they source innovation from universities. This suggests that in general business does not even think to involve universities in innovation – in other words, there is little interconnectedness.

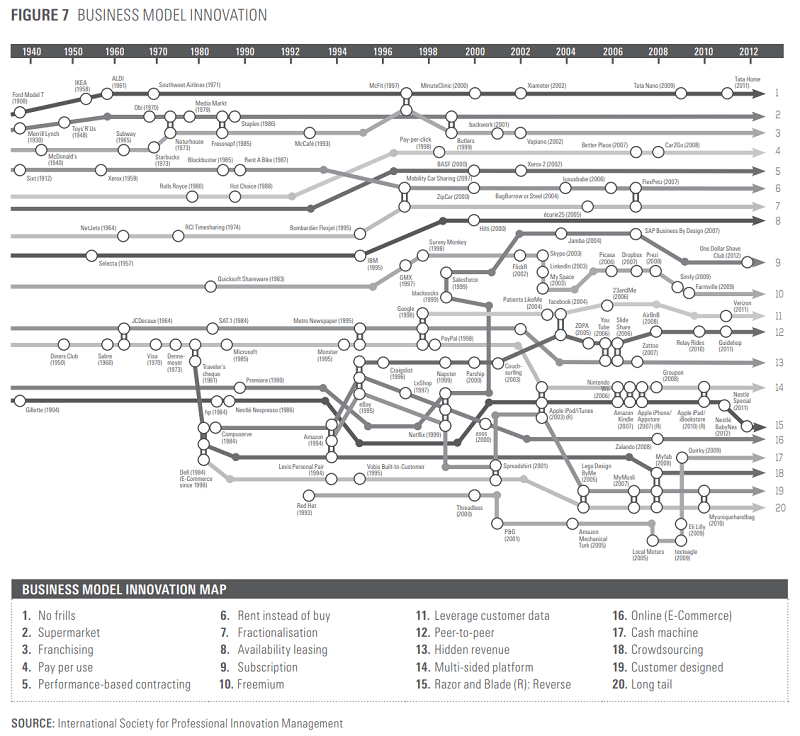

The interconnectedness required to form better relationships between universities and business is the same as that already used by business ecosystems – it is enabled by flows of information through technology and integration of systems. Contemporary business model design focuses on how to create value with others and take an appropriate share of value for ourselves (see Nielsen, 2017). Figure 7 is an illustration of business model design. In this context, there is a very definite role for universities as a part of that ecosystem of value creation. But how can these work together to create an ecosystem of mutual value creation?

Working Together

The future of both universities and business is in transcending boundaries between organisations – between sectors, between silos, between working. There are a number of challenges to developing an ecosystem in which the academic world and business world not just co-exist but actively collaborate (see Stokes, 2017). In order for connections between these two worlds to be meaningful they must be visible and clear, so that they can be further developed. This is important because different people think in different ways. For example, some people are drawn to the academic world and some to the business world. We ask, what interests these different people, what excites them about their work, what do they value? These core personal philosophies are framed by people’s environment – the structures of their workplace, the reward mechanisms and organisational ways of thinking. The institutionalisation of these philosophies has a profound impact on how people go about being connected.

As outlined by Stokes (2017), one of the challenges to developing the ecosystem is opposing timeframes. The constraint of short (business) versus long (universities) timeframes is a simple and soft constraint, one that can be quite easily worked around. It means thinking differently about research design (see section six). Another challenge is the rigidity of the structures of the commercialisation and intellectual property efforts in universities. Again this is a constraint that can be worked around.

In addition to constraints to working together there are connections – already academics and business are tied, and these ties provide some potential domains for value creation. One of these is education. The academic-business interaction is, I think, unique, in its feedback loop. Rather than a lecturer imparting knowledge to a student, in business there is a focus on postgraduate and executive education. Many executive educators report that they learn a lot from their students: the positive feedback loop, where relevant education is enabled by insights from those being taught, creates faster change. Similarly, the feedback loops mean that lessons learned in business can be applied in university structures like commercialisation. If lessons and experience in entrepreneurialism and innovation are embedded in business faculties, these lessons can then be applied across the university. While currently, in the most part, university commercialisation activities are a constraint, it is an area in which business faculties can take the lead, because they best understand, out of all faculties, the issues around innovation and business. Some universities are beginning to embed a Graduate Certificate in Commercialisation into their PhD programs. This furthers the concept of transdisciplinarity, recognising that many of the capabilities of business not just can, but must, be applied across universities to develop innovation and places the business faculty at the core of the ecosystem.

Business model innovation is an important domain, because innovation is not necessarily in technology but rather in and around what are the new models that are applying. There are many ways in which academic insights can be applied in a business context. In quantitative areas there are many ways in which network analysis and network science, among other domains, can be applied very effectively in business model innovation. These are beyond the capabilities of many organisations, including many of the large consulting firms, but within the capacity of universities and provide understanding of the issues around business model innovation within industries.

For universities and business to develop a stronger relationship it is important to recognise that collaboration is a capability. It starts from a mindset: a way of thinking, and is supported by skills, processes and structures. These range from the technological aspects of how to expose information, the processes for trust building, and how to understand the issues around effective business collaboration. These should be core capabilities that are a focus for business faculties so that they a source of excellence in understanding in which they ask and answer: what are the processes; what are the structures; what is the mindset; how can we teach this; how can we model this; how can we understand the collaboration capabilities that can be applied to businesses, to other faculties in the university, to the students and the people we work with?

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is an interesting lens through which to examine the idea of the business ecosystem because it offers many opportunities for engagement. It is a particularly useful example of the benefits and application of value-creating relationships, particularly in academic–business relationships. More and more large businesses are looking to the entrepreneurial sector to understand what they need to do to keep up in an extremely dynamic, fast moving world.

There are many entrepreneurial courses across Australia. MBAEs – MBAs with entrepreneurial courses, some of them entrepreneurial degrees themselves – but not all of them are run in business faculties. In fact, engineering faculties often run entrepreneurship programs. Entrepreneurship is applied quite differently in different domains, be it in fashion, or in medicine, or in information technology and, therefore, approach collaboration differently. But business faculties can, and should be, involved across all the schools in the university to drive innovation.

There are broadly two major frames for how startups are institutionally assisted: acceleration and incubation. Acceleration is the idea where over a set period of time, often three months, sometimes up to six months, new ventures are assessed and provided with resources, mentorship, connections, and relationships. One such example is the University of Melbourne Accelerator Program, in which startups that have originated from within the university are provided with skills, mentoring and a community in which networks are fostered.

Incubation is the provision of space and support, over an undefined period of time, in order to develop ideas and connections to be able to drive value. Cicada Innovations, which is owned by UNSW, the University of Sydney, UTS and ANU, has been voted the best business incubator in the world by the International Association of Business Incubators.

These programs are not necessarily run by business faculties. Rather, there is a proliferation of different structures around entrepreneurship in universities in Australia, with some based in business faculties, others run by engineering or computer science faculties, and others independent of any one faculty, or with ties to business. While no one model is preferable, clearly business faculties need to be able to bring to bear the full breadth of their capabilities to ensure that these kinds of entrepreneurship programs have the greatest chance of success.

Other entrepreneurship activities in universities are more aligned with venture capital organisations, for example, Uniseed, a joint effort by the University of Melbourne, the University of Sydney, UNSW, the University of Queensland and the CSIRO that funds medical, biotech and other research. Uniseed is essentially a separate organisation, with its board run by the universities and its activities funded by the universities. It has been able to provide healthy internal rates of return on the funds deployed in these ventures. This kind of venture moves beyond traditional commercialisation to providing, in addition to funds, networks, connections, and support.

Entrepreneurism also suggests a new way of combatting an old problem, that is, new metrics to measure the impact of a business faculty. Instead of measuring success by the number of graduates who are employed and their starting salaries, new measures could assess how many startups have been formed, how many have lasted for three years or more, what has been their financial success, what has been the trajectory of those startups, what is the degree of collaboration across the university, what are the number of jobs created.

Collaboration is a Capability

According to Norman and Ramirez ‘the only things that matter in the economy are knowledge and relationships.’ This has become increasingly true since Norman and Ramirez first wrote these words – everything else has been commoditised. Knowledge, expertise, capability, innovation – cannot be connected without the relationship. This why the ability to collaborate must be a core competence and capability of universities and business faculties.

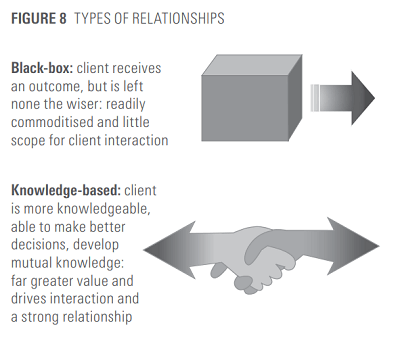

There are different styles of relationships, and in the range from a commoditised to a collaborative relationship, much relies on openness to new opportunity, the degree of trust and relationship scope. Universities come to this from a good starting level of trust, credibility and openness to exploration. But they must also be move their partners’ attitudes more and more to the collaborative: academic–business relationships must shift from a black box relationship to one which is a true knowledge-based relationship. Such a relationship must be characterised by both parties being more knowledgeable as an outcome (the positive feedback loop, discussed above). This is illustrated in Figure 8.

There are different styles of relationships, and in the range from a commoditised to a collaborative relationship, much relies on openness to new opportunity, the degree of trust and relationship scope. Universities come to this from a good starting level of trust, credibility and openness to exploration. But they must also be move their partners’ attitudes more and more to the collaborative: academic–business relationships must shift from a black box relationship to one which is a true knowledge-based relationship. Such a relationship must be characterised by both parties being more knowledgeable as an outcome (the positive feedback loop, discussed above). This is illustrated in Figure 8.

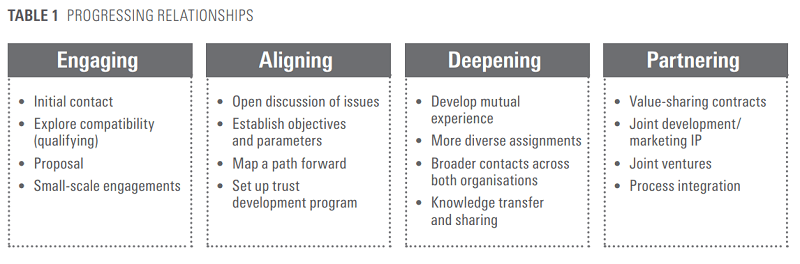

Building such relationships is based on initial engagement, alignment, deepening of the relationship and finally partnering. These steps are outlined in Table 1.

Often universities make the mistake of wanting to become partners right away, without understanding that it is a journey. Perhaps because of this, very few Australian organisations even think of universities as places to look for innovation.

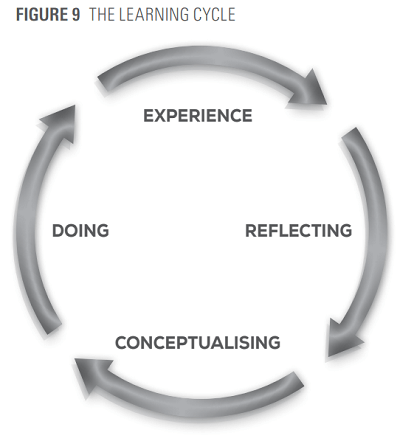

David Kolb’s learning cycle illustrates this cycle of knowledge development (see Figure 9), framing the ideas of doing, experiencing, reflecting and conceptualising. In a crude sense, this cycle shows a divide in learning experiences of business and academia. Business is concerned with the doing and experiencing; academia with the reflecting and conceptualising.

David Kolb’s learning cycle illustrates this cycle of knowledge development (see Figure 9), framing the ideas of doing, experiencing, reflecting and conceptualising. In a crude sense, this cycle shows a divide in learning experiences of business and academia. Business is concerned with the doing and experiencing; academia with the reflecting and conceptualising.

Despite its somewhat basic approach, the learning cycle framework suggests that the knowledge-development loop within the business and academic world relationship needs to be linked together. In an ideal collaboration and partnership, universities and businesses would look to each other to be part of knowledge development and develop their own knowledge capabilities, in partnership, drawing on each other’s strengths.

Considering the specific capabilities required to develop the potential for academic–business collaboration, it is critical to identify first, what is the aim? What the relationship is designed to uncover and achieve is not always clearly articulated, or understood, or communicated within business faculties and the broader university. For example, academics want the publication of research, which is of no interest to business. Ideally, business and academics can develop a relationship in which they both get what they want, but this can only be achieved if they first focus on a shared, common vision of what they want to achieve.

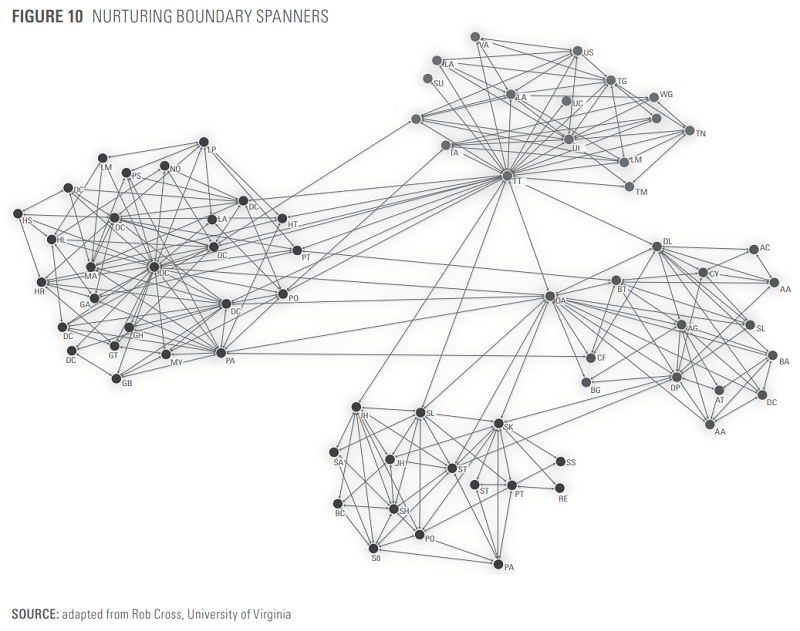

As for many aspects of organisational change, key individuals can make significant change. These are boundary spanners, who are independent of organisational silos and bring people together (see Figure 10). Social network analysis (see, for example, Stuructural Holes, Ron Burt; The Hidden Power of Social Network, Rob Cross) identifies this phenomenon in which some people are able to span boundaries, be they across departments, organisations, faculties, or cultures. Not everyone has this capacity and this is equally true of universities – not all academics will be good at engaging with business, while for others this will be a strength. Therefore, it is important that universities develop a strategy of identifying and supporting the boundary spanners, through reward mechanisms and resources. This may even mean creating a specific role for a boundary spanner.

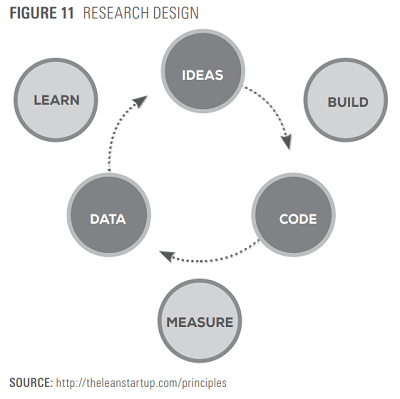

A key collaboration capability is to be able to identify a research topic. This cannot happen in isolation and requires academics to be exposed to current issues in the business world. Businesses are often not aware of the parameters of the academic world and researchers need to assist business in navigating the gaps in the literature and the potential for collaboration beyond consulting. Of particular importance is research design, that is designing research so that it works for business. Eric Ries (2011), in his book The Lean Startup, identifies the key elements as generating ideas, building something, measuring results, collecting data and getting feedback. These elements form a central loop of doing and learning, not dissimilar to the Kolb Learning Cycle.

A key collaboration capability is to be able to identify a research topic. This cannot happen in isolation and requires academics to be exposed to current issues in the business world. Businesses are often not aware of the parameters of the academic world and researchers need to assist business in navigating the gaps in the literature and the potential for collaboration beyond consulting. Of particular importance is research design, that is designing research so that it works for business. Eric Ries (2011), in his book The Lean Startup, identifies the key elements as generating ideas, building something, measuring results, collecting data and getting feedback. These elements form a central loop of doing and learning, not dissimilar to the Kolb Learning Cycle.

The advocates of this lean startup movement claim to take up a scientific approach: they form a hypothesis, design an experiment, learn from that experiment, and then change and adapt based on the results. However in the startup world they do this over a day, unlike the academic world where these activities would take place over three years. Herein lies an opportunity to design research that can transcend the challenges, by incorporating short-term iterations into longer-term research initiatives. A parallel can be seen in the medical world where there is a shift from clinical trials, in which a hypothesis is formed and tested over a lengthy trial period, to so-called adaptive clinical trials, where the trial is changed almost daily on the basis of data as it’s collected. This adaptive model is ideally suited to academic–business collaboration because it involves day-to-day learning but also fosters long-term research frames and outcomes.

Finally, it is important to consider leadership. According to James Carse: “Finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with boundaries”. Business faculties have the potential and the possibility to play with the boundaries between organisations; between domains of study; between capabilities today. And in moving to that space, the question is: who is going to lead on that path; is it going to be the business faculties; is it going to be the startups; is it going to be the people in big business? In my view, businesses are not going to take the lead because they do not see the value that lies within, so leadership must start with universities.

Essential for industry leadership is vision. What is it that is worth creating? What are the foundations for that vision? Understanding the roadblocks and finding the paths around those roadblocks is where leadership will make a difference.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly there are challenges to developing more meaningful and effective academic–business collaboration. While it is important to acknowledge them and understand them, it is also critical that we recognise that they can be overcome. The way forward lies in connectedness, in relationships, capabilities and leadership. The potential for academic–business collaboration is immense. Not only is it likely to change the university world, and the business world, but it has implications for society more widely in its capacity to foster national prosperity. These are exciting times if we build the right foundations from which to leap forward into the future.

References

Carse, J. (1986), Finite and infinite Games: A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility, Ballantine Books, New York.

DIIS/ABS

Mullis, K. (1999), Dancing Naked in the Mind Field, Bloomsbury, London.

Nielsen, N. (2017), ‘Value exchange in university–industry collaborations: European experiences’, Academic Leadership Series, Vol. 8, pp. xx-xx.

Norman, R. and Ramirez, R. (1993), ‘From Value Chain to Value Constellation, The Harvard Business Review, July–August, pp. 65–77

Ries, E. (2011), The Lean Startup, Crown Publishing, US.

Stokes, G. (2017), ‘Improving collaboration between commerce and business researchers to improve innovation’, Academic Leadership Series, Vol. 8, pp. 102–105.