The future of work: better decisions supported by computers and professionals

This morning I gave the opening keynote on The Future of Work at the Chartered Accountants Thought Leadership Forum on Future Proofing the Profession: Preparing Business Leaders and Finance Professionals for 2025, the third year in a row I’ve given keynotes on different topics at the Thought Leadership Forum.

In my keynote I went into depth on the forces shaping the future of work and the action that we can take today to help create a better future. One of the topics I raised was about the future of decision-making in a world of increasing automation.

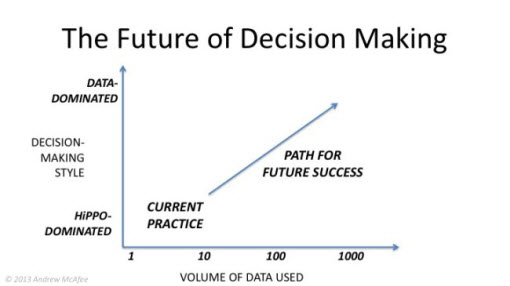

Andrew McAfee of MIT has created a simple illustration of the path to better decisions.

Source: Andrew McAfee

McAfee makes the case that across domains decisions are better made by data-driven algorithms than by humans:

Data-driven decisions, predictions, and diagnoses are much better than those that come from human intuition and HiPPOs (the ‘Highest-Paid Person’s Opinions’). The research is overwhelming on this point. HiPPOs might be good for some things, but their crystal balls just don’t work very well. The soulless output of a data-driven, mechanistic algorithm is demonstrably and significantly better, in domain after domain. So HiPPOs should become an endangered species.

Definable and tractable decisions

This scenario does require decisions that are definable and tractable. In specific decision domains where sufficient data is available, algorithms absolutely can and will evolve to the point that they surpass human judgment.

However if the decision domain is not clearly defined or there is insufficient relevant data, algorithms cannot be effective. A prominent example is an organization’s strategic positioning. Any data-driven model of industry structure and potential decisions will be based on implicit assumptions by the creator of the algorithm.

Higher-order cognitive models are required, and while many humans will not outperform random strategic decisions, some will, in which case they potentially justify being the highest-paid person.

Preference for human decisions

There is also the reality that even if computer models are demonstrated to outperform human decisions, for the foreseeable future the majority of humans will not give away their decision-making roles.

For example, it will be a long time before most citizens prefer decisions made by algorithms to those made by politicians, even if they hold those politicians in extremely low regard.

Adding value to human decision making

Which brings us to the critical role of adding value to decision-making, a key topic of my first book.

Speaking at a conference for accountants, I have to point to their long-established role of supporting better management decisions (as well as making sure that the accounts add up correctly).

One of the oft-missed points about ‘Big Data’ is that it requires interpretation and effective communication to support better human decisions. While much data is applied in algorithms, there are also domains in which data supports human decisions (even if that is not the optimal structure).

Professional roles in supporting decisions in a data-driven world

The true professional is one who can communicate data in a way that it changes the thinking of the highest-paid person (or other decision-maker). This is a human art requiring relationship skills that far transcend those of computers.

While many jobs will disappear, a growing category of jobs is those who intermediate between data and algorithms, and humans who make decisions. This is about understanding and impacting cognition as much as understanding data. Effective visual communication will be critical. Empathy will be essential for important decisions.

So in a world in which an increasing proportion of decisions will be made by machines, there will also be a growing role for those who effectively support human decisions.