Critical issue: Will the fertility rate in the developed world continue to increase?

I recently appeared on the Morning Show being interviewed about the future of the family. Click on the image below to see a video of the segment.

One of the interesting topics we discussed was trends in the fertility rate.

Developed countries around the world experienced a massive baby boom in the 1950s, which then fell dramatically to see the fertility rate fall to below the replacement rate in almost every developed country in the world.

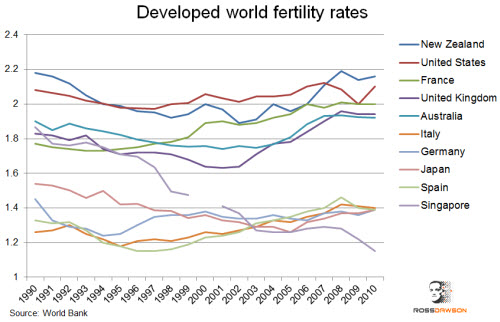

However the fertility rate has been rising in many developed countries over the last years, in contrast to the faster-than-expected decline in the fertility rate in developing countries, as shown in the chart below.

The trend is consistently down in Singapore. The US, which has had the highest developed world fertility due to its growing Latin American, Catholic popluation, is in fact experiencing a relative ‘baby bust‘ at the moment.

However for the last decade – and in fact longer in some cases – the fertility rate has been increasing in other developed countries.

Spain and Italy in particular, while they have among the lowest fertility rate of Western countries, this has risen fairly consistently for the last decade.

The UK has seen fertility rise from 1.65 to 1.9, Australia has had a boom which has now flattened, and France’s fertility rate is now almost at replacement rate.

I have seen no good explanations as to why the fertility rate is increasing so consistently across developed countries, though I’d be delighted to be pointed to any.

As I suggest in my interview, there is certainly a degree of cyclicality to fertility, as social mores shift. The social rift in the 1960s pushed fertility rates dramatically down as women adjusted to new roles and opportunities. Yet at a certain point the fundamental human propensity to procreate led to men and women changing their priorities.

There is no question that birth rates are correlated to people’s feelings of economic security. It is interesting that even in the uncertain economic times of the last 5 years fertility has not fallen. Perhaps for many, while they are concerned about their jobs and earnings, they do feel they have sufficient resources to bring children into the world.

From here, a key question is whether these fertility rates will continue to increase. They are unlikely to significantly exceed the replacement rate of 2.05, so immigration will still be necessary for economic vitality in many Western and developed countries, however the pressure may be eased.

This is a critical issue that the government, business, and social sectors will need to keep strongly aware of in coming years.