The dilemma for professionals: How do you respond to anonymous leaks and slander?

Today’s Australian Financial Review has an interesting article titled “Watch out for the spook in the navy blue suit” which looks at how professionals can respond to anonymous slander, quoting me and a few others.

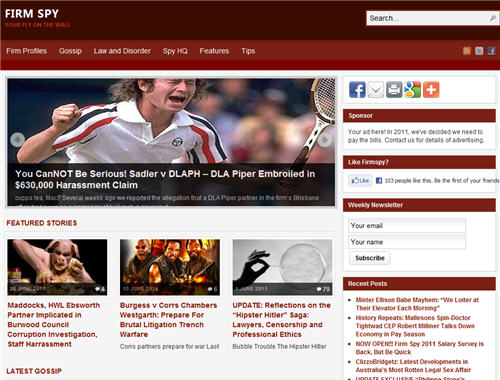

It looks at FirmSpy, which is a site that provides gossip about Australian professional firms, notably law firms and the local arms of the Big 4 accounting firms. FirmSpy provides insights into internal issues such as bullying, sexual harassment, and staff satisfaction and turnover, resulting in Australian Financial Review calling it “Australia’s own Wikileaks for lawyers and accountants”.

For those accused of wrongdoing, there are limited possibilities for response. The article says:

Social media strategist Ross Dawson says it is inevitable that more sites such as Firm Spy will spring up and organisations need to decide how they will deal with cristicim that can be from anonymous sources, or through social media such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn groups.

“This is is one of the challenges of the online world, and there are a limited range of responses to it,” says Dawson, chairman of Advanced Human Technologies.

The possible responses are:

1. To contact the site and ask it to take down offending material.

This is pretty unlikely to be useful, though if you can convince the publisher it is incorrect they might do something. Firm Spy now offers a right of response to firms before publication, and says it does not publish information that turns out to be incorrect.

2. To threaten legal action for defamation.

In the case of anonymous sites this can only be delivered through anonymized remailers, and legal action can only be taken if there is someone who can be identified, which is very difficult. However a FirmSpy representative says they expect to be uncovered, at which point legal proceedings can be launched. However, as in point 4 below, this will simply highlight the issue to the public.

3. To conduct internal witch-hunts to find who has leaked material.

This implies the information is correct, so this is a stop-gap measure at best.

4. To publicly respond to the accusations.

This a very dangerous strategy as it most often brings far more attention to the slurs than they would have received otherwise. However if you do you should do that on a similar social platform to where they originally appeared. The journalist used the example I gave of the CEO of Carnival Cruises’ YouTube videos responding to videos taken by passengers.

The article goes on:

“Being engaged in social media gives you a right of response… competing by press release is singularly ineffective,” says Dawson.

Overreacting could make an ugly situation even worse, he warns, pointing to Nestle’s action to remove a Greenpeace protest video, which spoofed a Kit Kat ad in a campaign against the use of palm oil.

Some Australian law firms have blocked FirmSpy on work computers, however they soon realized it was pointless as traffic to the site jumped 50% after the bans, and they allowed access again.

Dawson says the emergence of whistleblowing sites can have a positive impact – and not just for those who need to get something off their chests.

“I think transparency of institutions is a good thing. It is also an inevitable trend,” he says.

The article goes on to look at social media monitoring and reinforcing the messages of positive response, which I cover in our social media strategy framework. The piece ends with a nice quote from a Deloitte executive who says:

“The day you can micro control your brand image is gone forever.”

Absolutely. We need to learn to live with transparency and the fact that sometimes things said about us will be unfair. In the reputation economy the genuinely positive will almost always outweigh the falsely negative. As long as we know how to engage and be seen.